AI’ll Be Watching You

August 9, 2024

min read

Summary

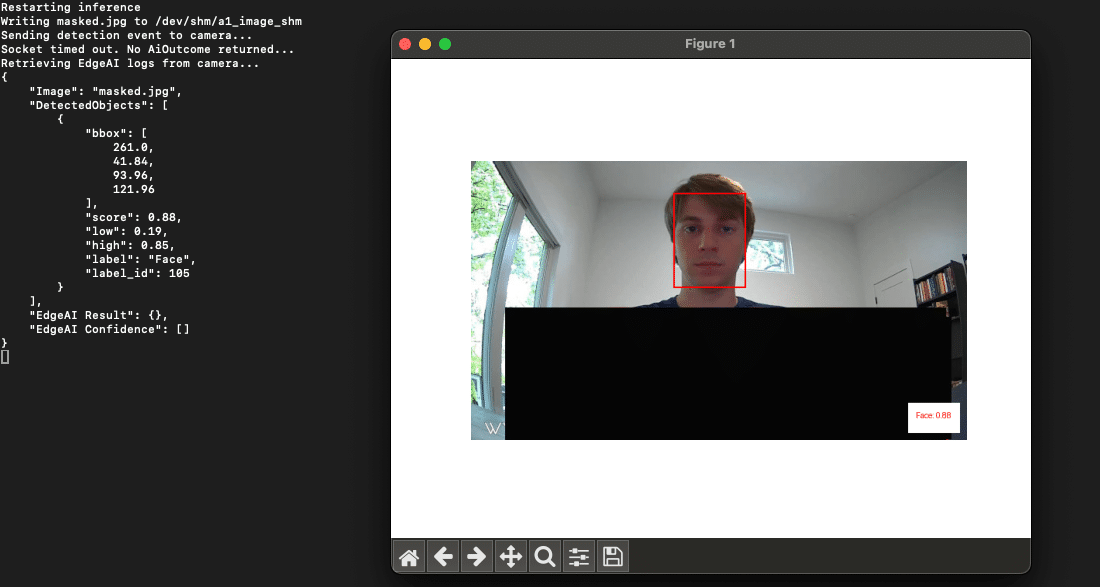

HiddenLayer researchers have recently conducted security research on edge AI devices, largely from an exploratory perspective, to map out libraries, model formats, neural network accelerators, and system and inference processes. This blog focuses on one of the most readily accessible series of cameras developed by Wyze, the Wyze Cam. In the first part of this blog series, our researchers will take you on a journey exploring the firmware, binaries, vulnerabilities, and tools they leveraged to start conducting inference attacks against the on-device person detection model referred to as “Edge AI.”

Introduction

The line between our physical and digital worlds is becoming increasingly blurred, with more of our lives being lived and influenced through an assortment of devices, screens, and sensors than ever before. Advancements in AI have exacerbated this, automating many arduous tasks that would have typically required explicit human oversight – such as the humble security camera.

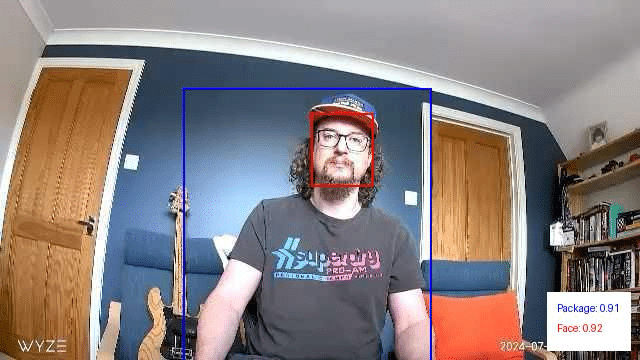

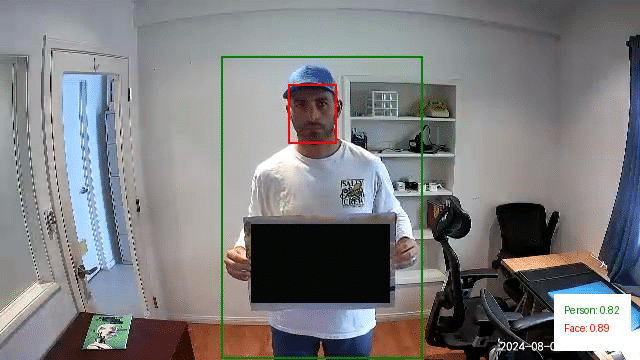

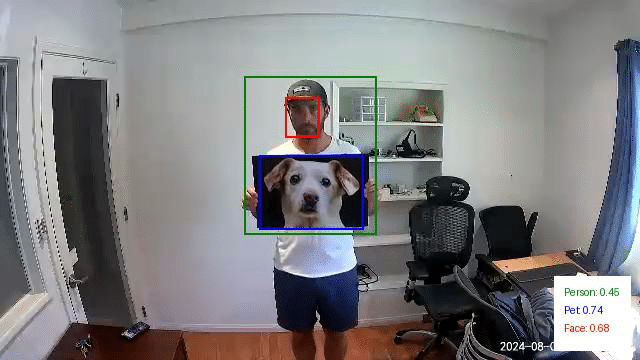

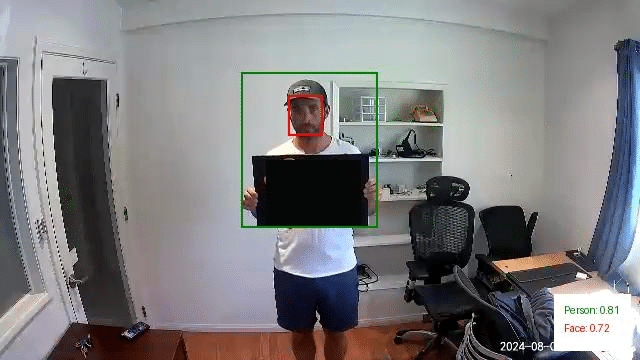

As part of our mission to secure AI systems, the team set out to identify technologies at the ‘Edge’ and investigate how attacks on AI may transcend the digital domain – into the physical. AI-enabled cameras, which detect human movement through on-device AI models, stood out as an archetypal example. The Wyze Cam, an affordable smart security camera, boasts on-device Edge AI for person detection, which helps monitor your home and keep a watchful eye for shady characters like porch pirates.

Throughout this multi-part blog, we will take you on a journey as we physically realize AI attacks through the most recent versions of the AI-enabled Wyze camera – finding vulnerabilities to root the device, uploading malicious packages through QR codes, and attacking the underlying model that runs on the device.

This research was presented at the DEFCON AIVillage 2024.

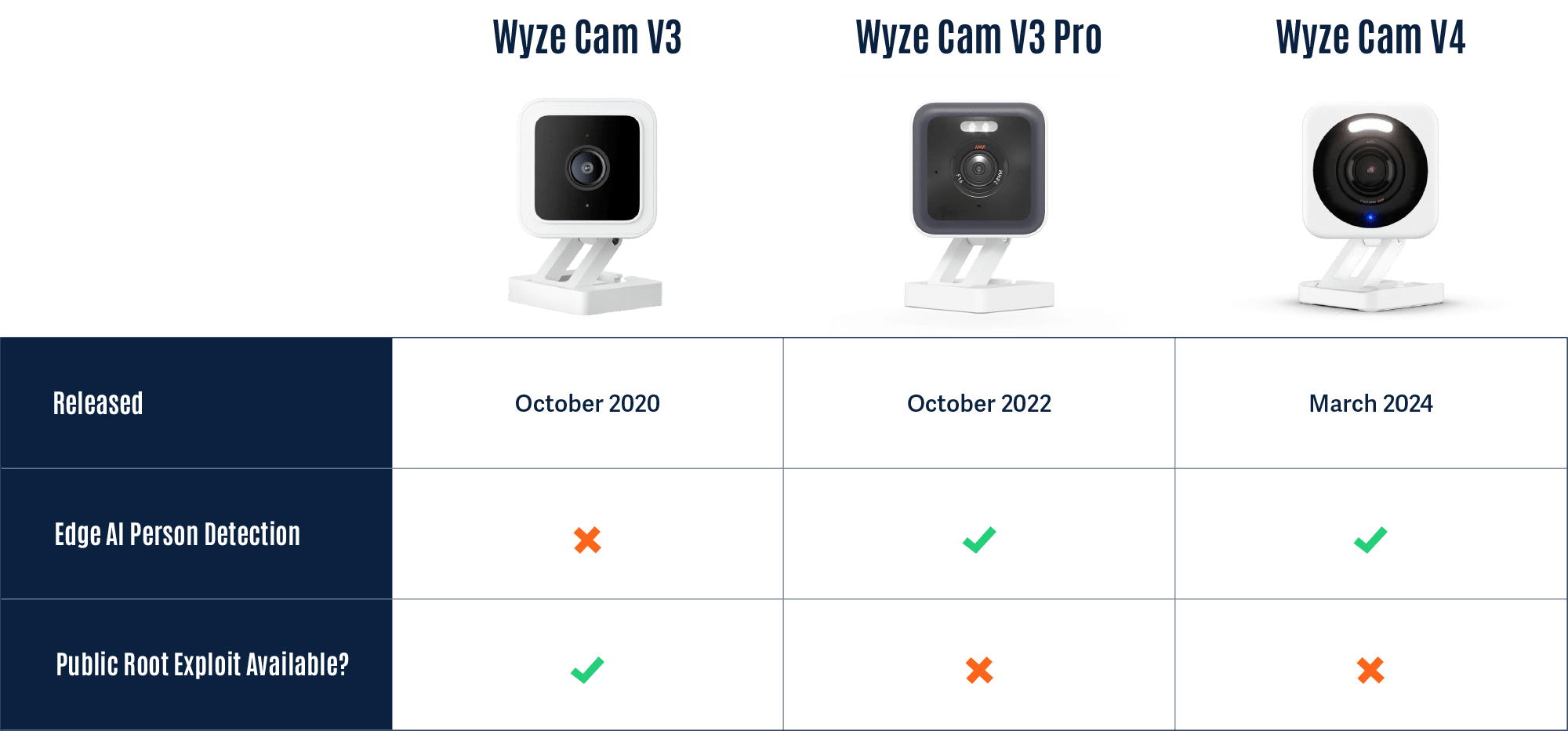

Wyze

Wyze was founded in 2017 and offers a wide range of smart products, from cameras to access control solutions and much more. Although Wyze produces several different types of cameras, we will focus on three versions of the Wyze Cam, listed in the table below.

Rooting the V3 Camera

To begin our investigation, we first looked for available firmware binaries or public source code to understand how others have previously targeted and/or exploited the cameras. Luckily, Wyze made this task trivial as they publicly post firmware versions of their devices on their website.

Thanks to the easily accessible firmware, there were several open-source projects dedicated to reverse engineering and gaining a shell on Wyze devices, most notably WyzeHacks, and wz_mini_hacks. Wyze was also a device targeted in the 2023 Toronto Pwn2Own competition, which led to working exploits for older versions of the Wyze firmware being posted on GitHub.

We were able to use wz_mini_hacks to get a root shell on an older firmware version of the V3 camera so that we would be better able to explore the device.

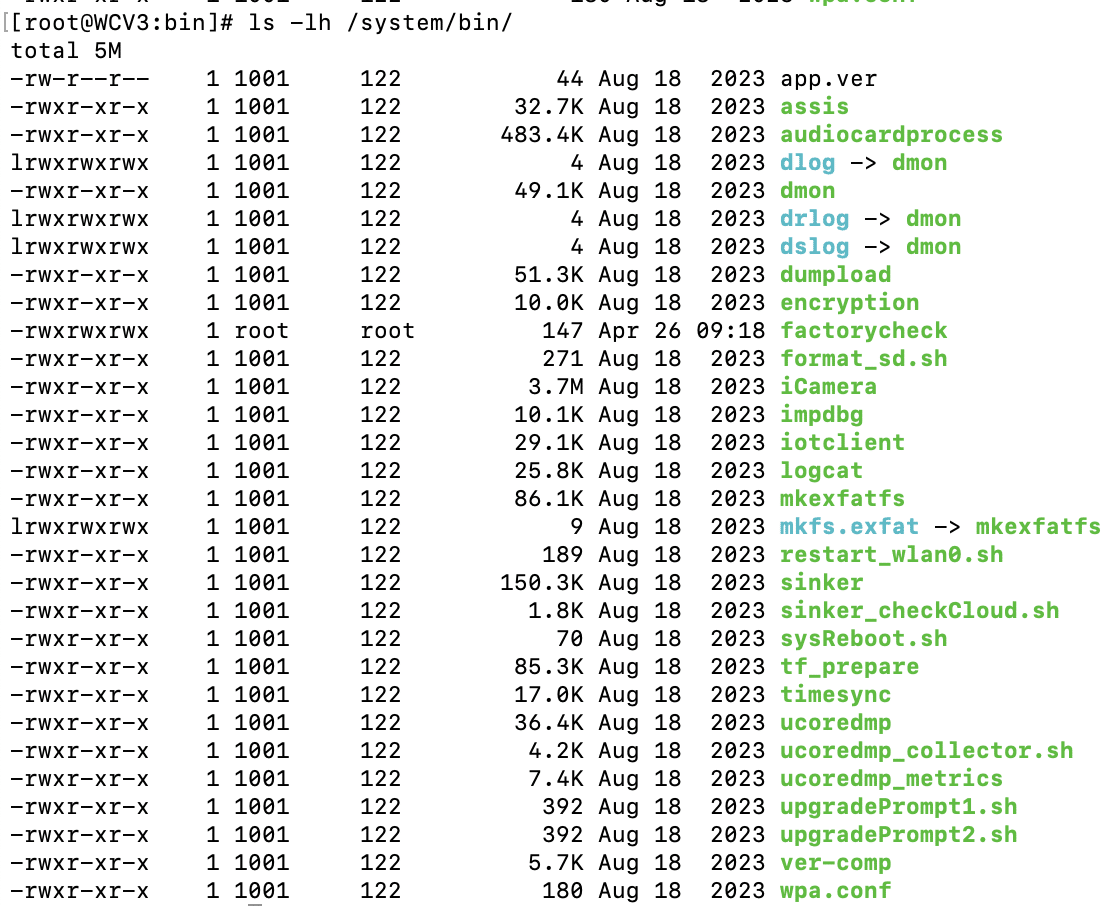

Overview of the Wyze filesystem

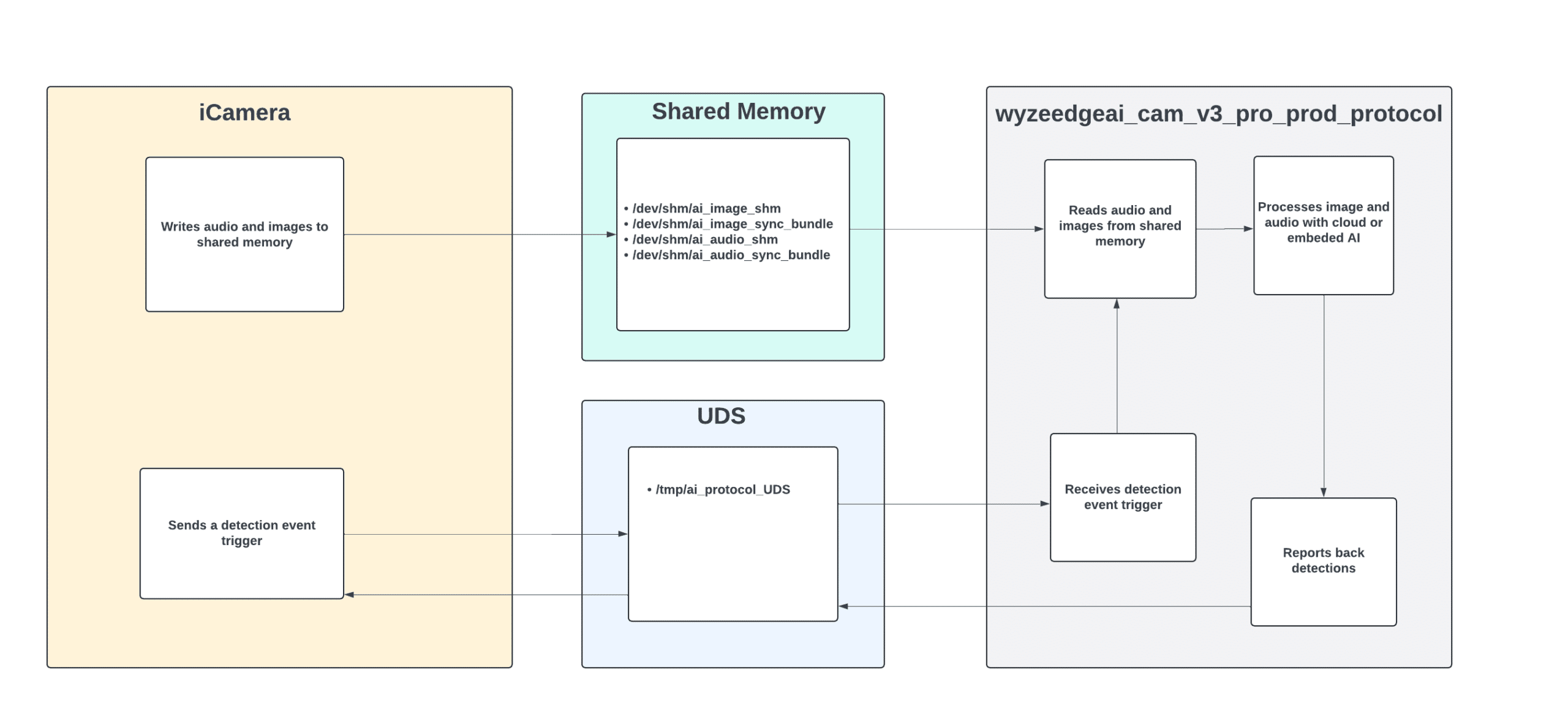

Now that we had root-level access to the V3 camera and access to multiple versions of the firmware, we set out to map it to identify its most important components and find any inconsistencies between the firmware and the actual device. During this exploratory process, we came across several interesting binaries, with the binary iCamera becoming a primary focus:

We found that iCamera plays a pivotal role in the camera’s operation, acting as the main binary that controls all processes for the camera. It handles the device’s core functionality by interacting with several Wyze libraries, making it a key element in understanding the camera’s inner workings and identifying potential vulnerabilities.

Interestingly, while investigating the filesystem for inconsistencies between the firmware downloaded from the Wyze website and the device, we encountered a directory called /tmp/edgeai, which caught our attention as the on-device person detection model was marketed as ‘Edge AI.’

Edge AI

What’s in the EdgeAI Directory?

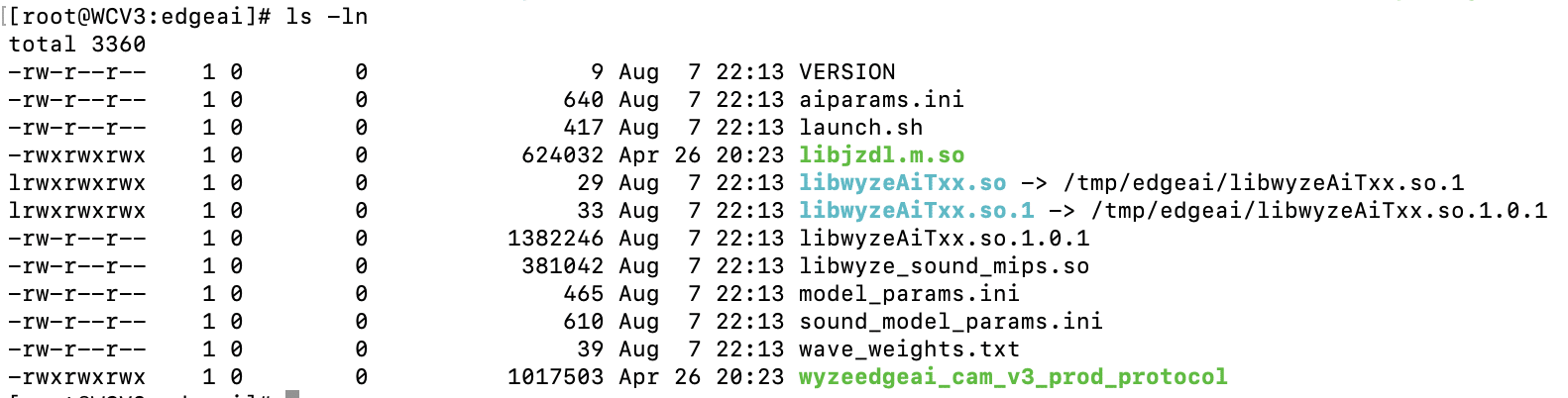

Ten unique files were contained within the edgeai directory, which we extracted and began to analyze.

The first file we inspected – launch.sh – could be viewed in plain text:

launch.sh performs a few key commands:

- Creates a symlink between the expected shared object name and the name of the binary in the edgeai folder.

- Adds the /tmp/edgai folder to PATH.

- Changes the permissions on wyzeedgeai_cam_v3_prod_protocol to be able to execute.

- Runs wyzeedgeai_cam_v3_prod_protocol with the paths to aiparams.ini and model_params.ini passed as the arguments.

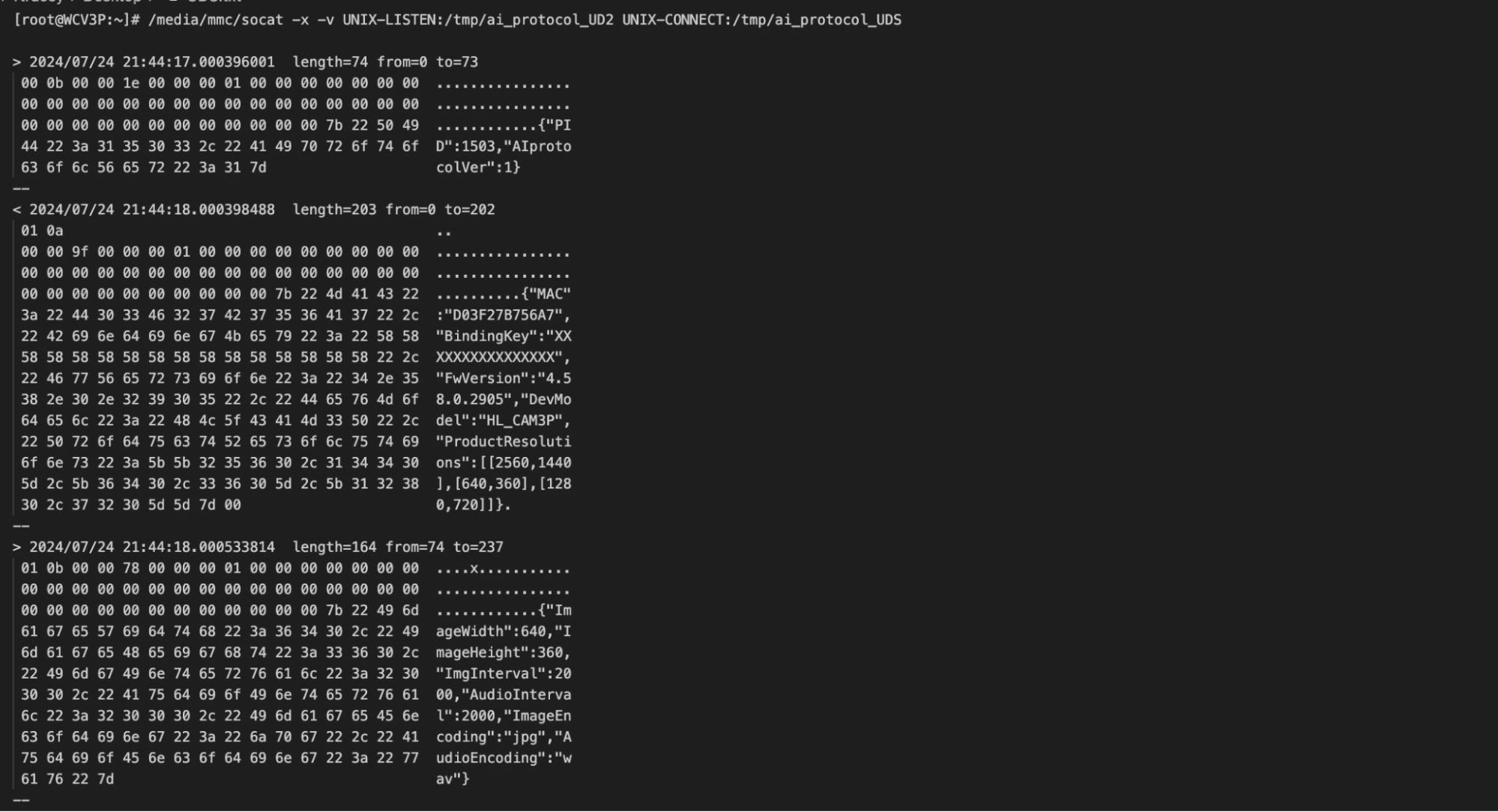

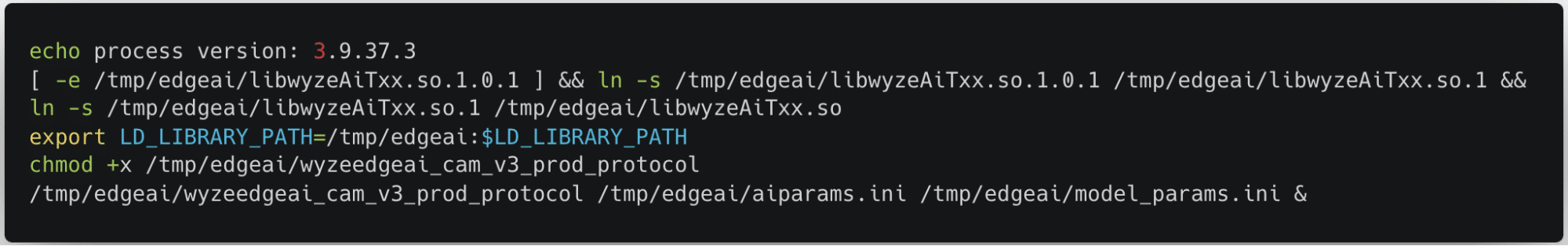

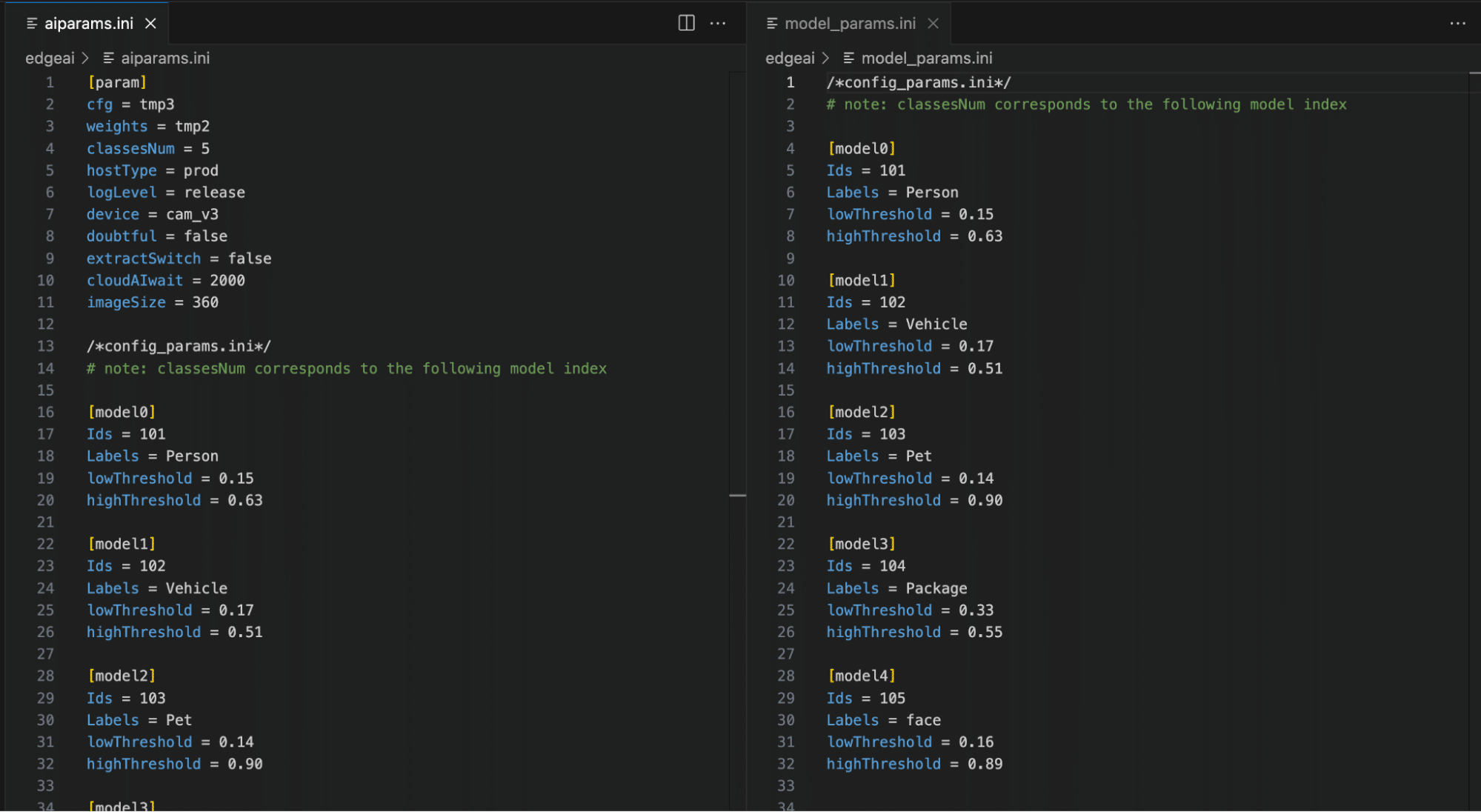

Based on these commands, we could tell that wyzeedgeai_cam_v3_prod_protocol was the main binary used for inference, that it relied on libwyzeAiTxx.so.1.0.1 for part of its logic, and that the two .ini files were most likely related to configuration in some way.

As shown in Figure 4, by inspecting the two .ini files, we can now see relevant model configuration information, the number of classes in the model, and their labels, as well as the upper and lower thresholds for determining a classification. While the information in the .ini files was not yet useful for our current task of rooting the device, we saved it for later, as knowing the detection thresholds would help us in creating adversarial patches further down the line.

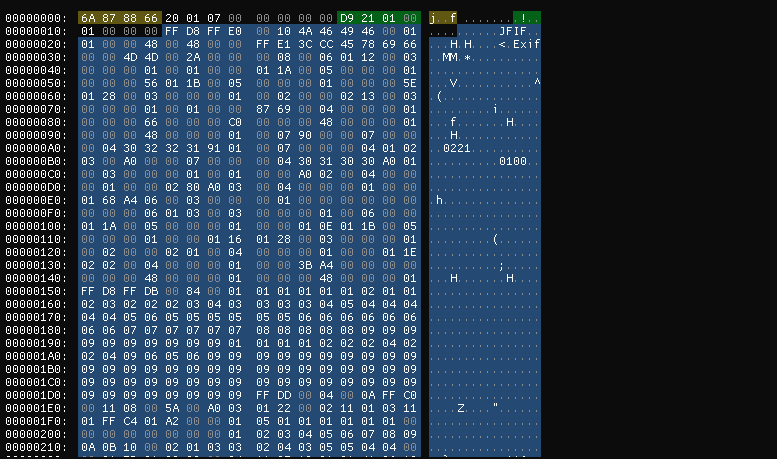

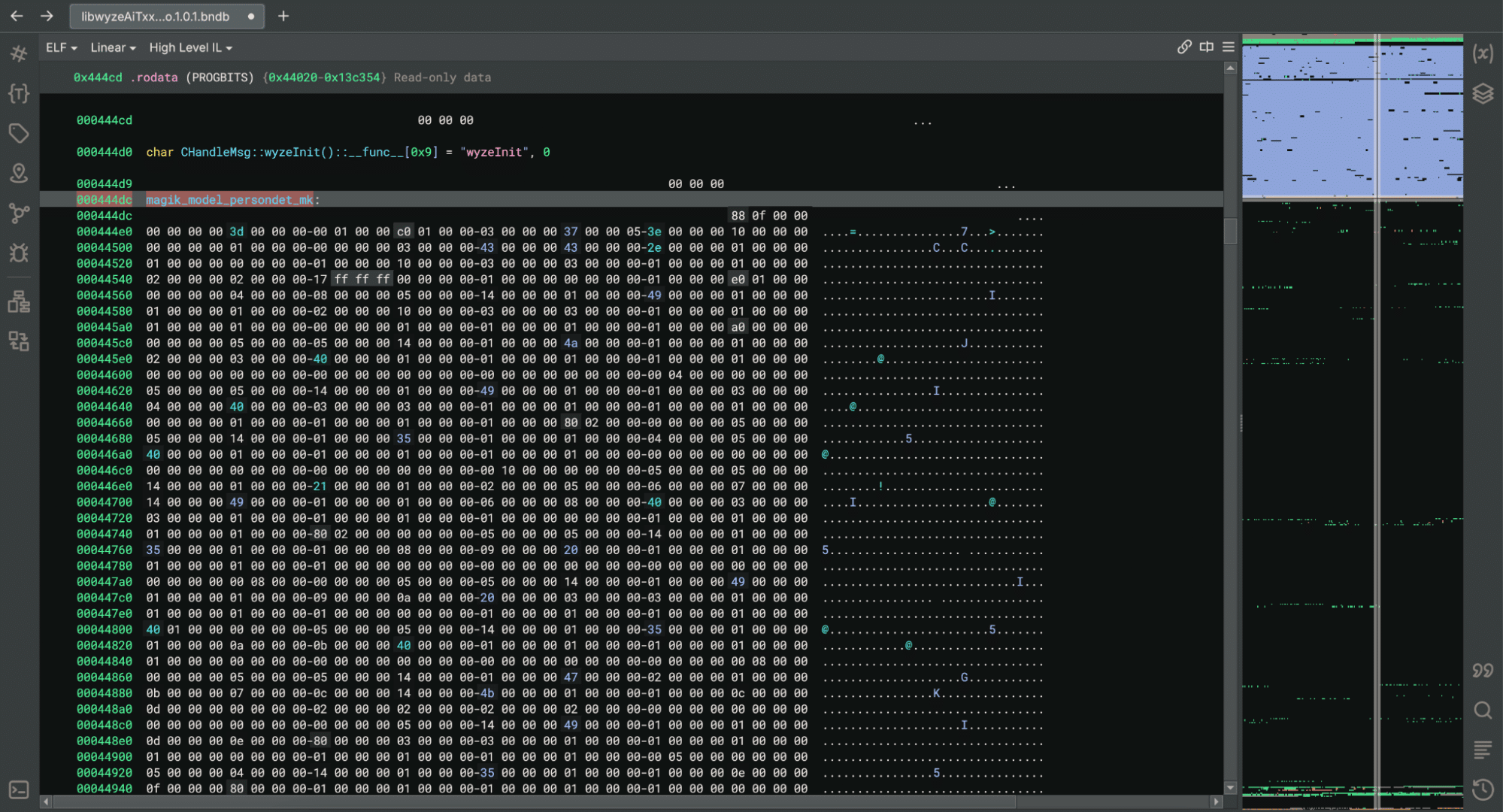

We then started looking through the binaries, and while looking through libwyzeAiTxx.so.1.0.1, we found a large chunk of data that we suspected was the AI model given the name ‘magik_model_persondet_mk’ and the size of the blob – though we had yet to confirm this:

Within the binary, we found references to a library named JZDL, also present in the /tmp/edgeai directory. After a quick search, we found a reference to JZDL in a different device specification which also referenced Edge AI: ‘JZDL is a module in MAGIK, and it is the AI inference firmware package for X2000 with the following features’. Interesting indeed!

At this point, we had two objectives to progress our research: Identify how the /tmp/edgeai directory contents were being downloaded to the device in order to inspect the differences between the V3 Pro and V3 software; and reverse engineering the JZDL module to verify the data named ‘magik_model_persondet_mk’ was indeed an AI model.

Reversing the Cloud Communication

While we now had shell access to the V3 camera, we wanted to ensure that event detection would function in the same way on the V3 Pro camera as the V3 model was not specified as having Edge AI capabilities.

We found that a binary named sinker was responsible for downloading the files within the /tmp/edgeai directory. We also found that we could trigger the download process by deleting the directory’s contents and running the sinker binary.

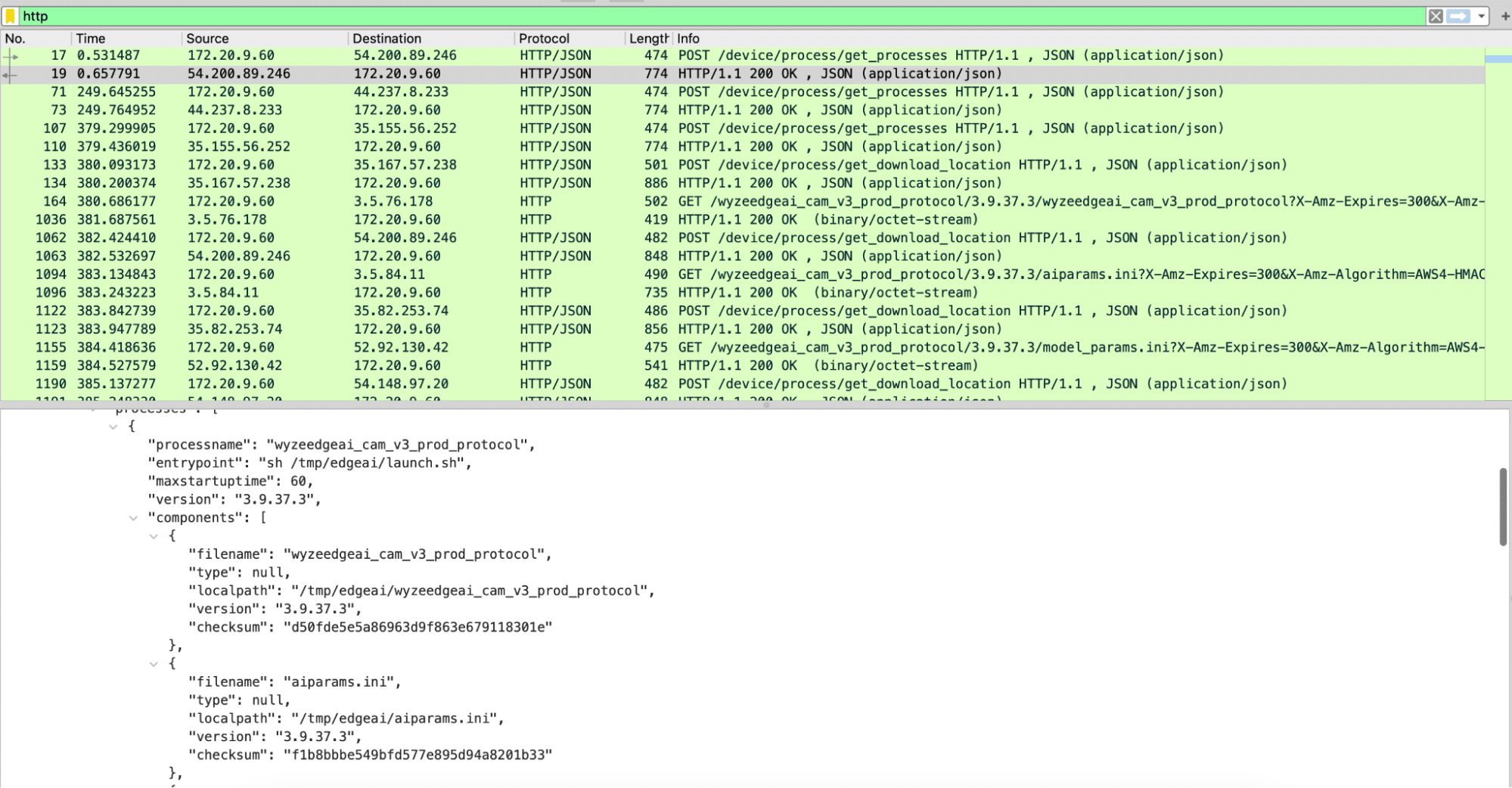

Armed with this knowledge, we set up tcpdump to sniff network traffic and set the SSLKEYLOGFILE variable to save the client secrets to a local file so that we could decrypt the generated PCAP file.

Using Wireshark to analyze the PCAP file, we discovered three different HTTPS requests that were responsible for downloading all the firmware binaries. The first was to /get_processes, which, as seen in Figure 6, returned JSON data with wyzeedgeai_cam_v3_prod_protocol listed as a process, as well as all of the files we had seen inside of /tmp/edgeai. The second request was to /get_download_location, which took both the process name and the filename and returned an automatically generated URL for the third request needed to download a file.

The first request – to /get_processes – took multiple parameters, including the firmware version and the product model, which can be publicly obtained for all Wyze devices. Using this information, we were able to download all of the edgeai files for both the V3 Pro and V3 devices from the manufacturer. While most of the files appeared to be similar to those discovered on the V3 camera, libwyzeAiTxx.so.1.0.1 now referenced a binary named libvenus.so, as opposed to libjzdl.so.

Battle of the inference libraries

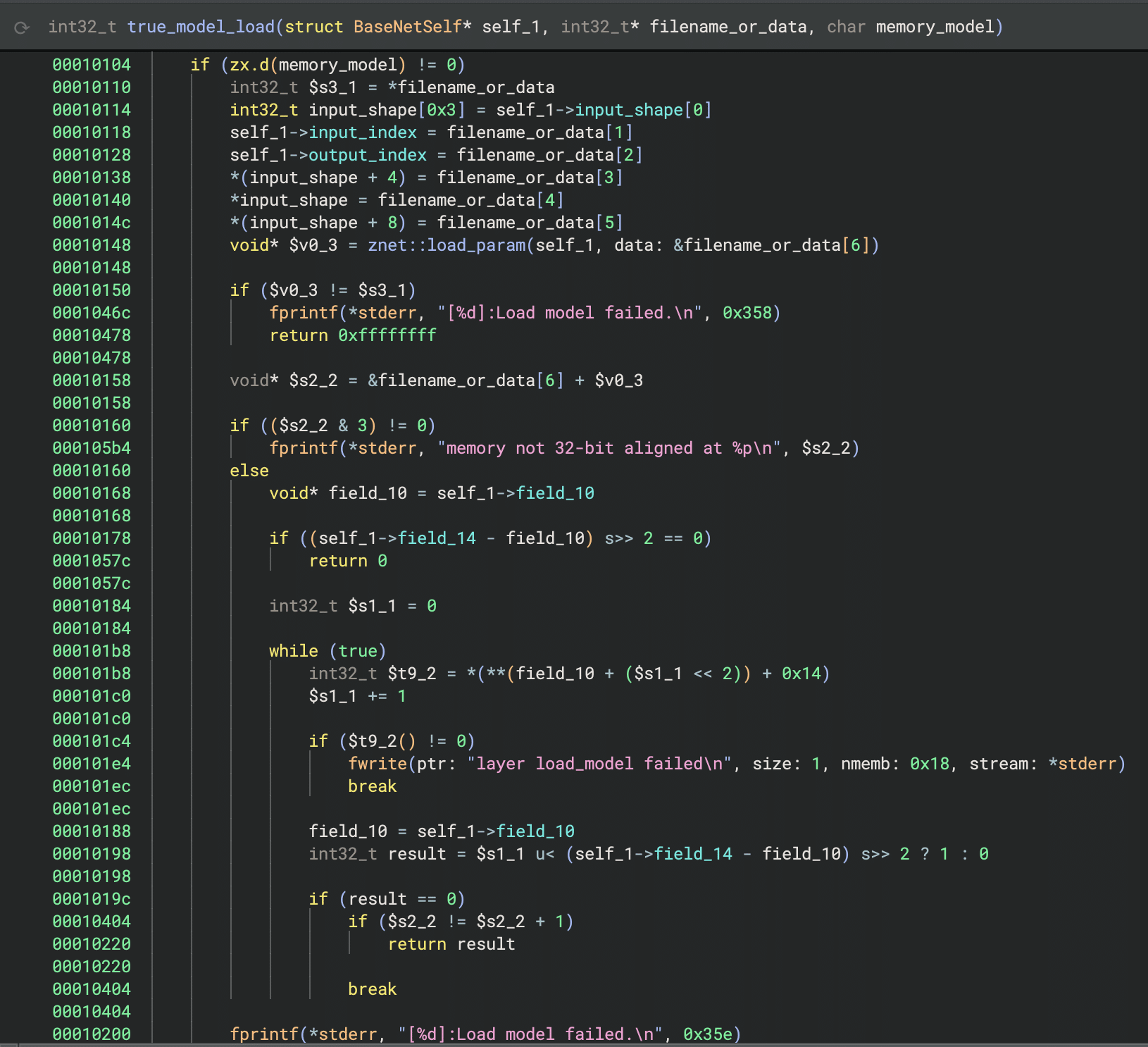

We now had two different shared object libraries to dive into. We started with libjzdl.so as we had already done some reverse engineering work on the other binaries in that folder and hoped this would provide insight into libvenus.so. After some VTable reconstruction, we found that the model loading function had an optional parameter that would specify whether to load a model from memory or the filesystem:

This was different from many models our team had seen in the past, as we had typically seen models being loaded from disk rather than from within an executable binary. However, it confirmed that the large block of data in the binary from Figure 5 was indeed the machine-learning model.

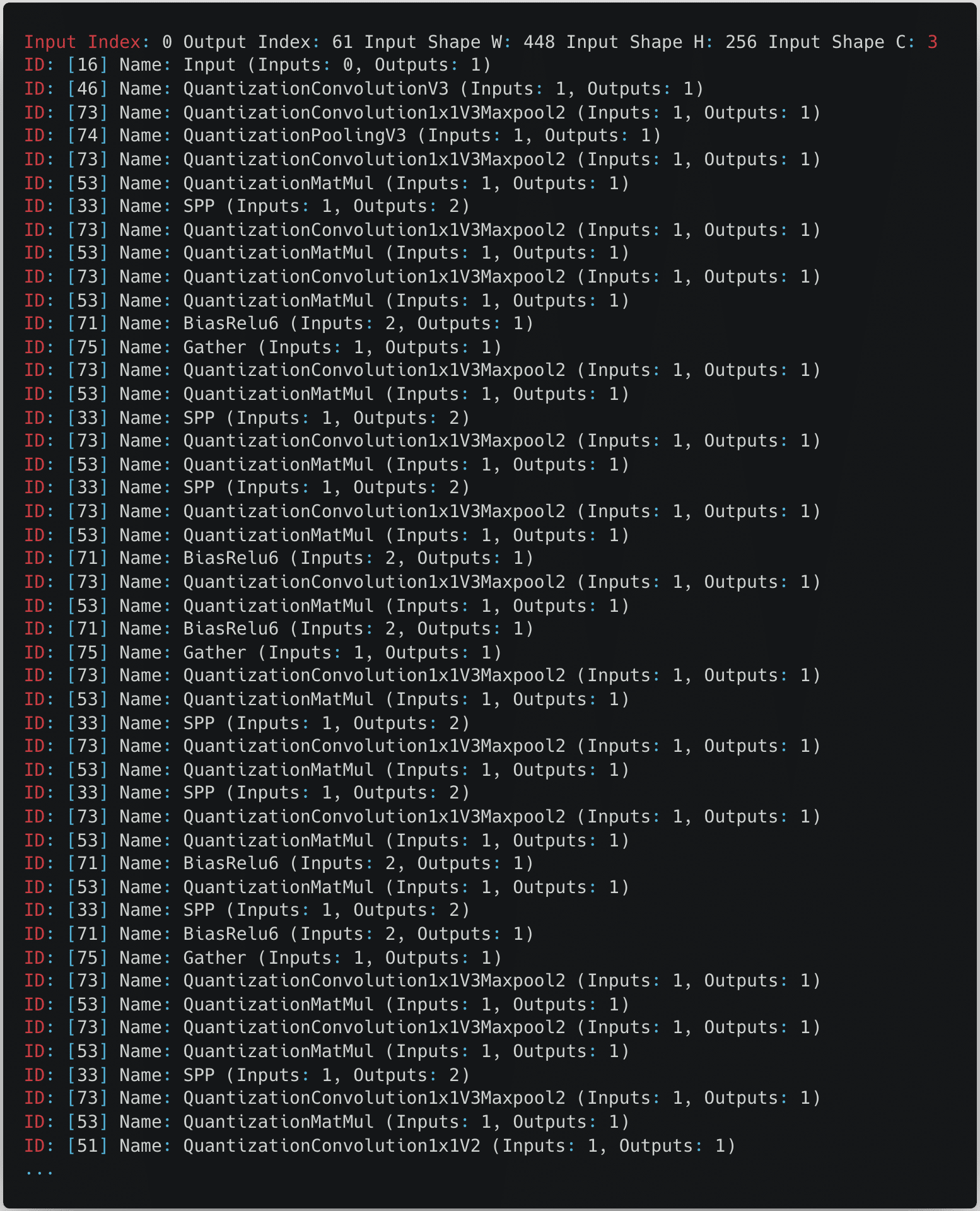

We then started reverse engineering the JDZL library more thoroughly so we could build a parser for the model. We found that the model started with a header that included the magic number and metadata, such as the input index, output index, and the shape of the input. After the header, the model contained all of the layers. We were then able to write a small script to parse this information and begin to understand the model’s architecture:

From the snippet in the above figure, we can see that the model expects an input image with a size of 448 by 256 pixels with three color channels.

After some online sleuthing, we found references to both files on GitHub and realized that they were proprietary formats used by the Magik inference kit developed by Ingenic.

namespace jzdl {

class BaseNet {

public:

BaseNet();

virtual ~BaseNet() = 0;

virtual int load_model(const char *model_file, bool memory_model = false);

virtual vector<uint32_t> get_input_shape(void) const; /*return input shape: w, h, c*/

virtual int get_model_input_index(void) const; /*just for model debug*/

virtual int get_model_output_index(void) const; /*just for model debug*/

virtual int input(const Mat<float> &in, int blob_index = -999);

virtual int input(const Mat<int8_t> &in, int blob_index = -999);

virtual int input(const Mat<int32_t> &in, int blob_index = -999);

virtual int run(Mat<float> &feat, int blob_index = -999);

};

BaseNet *net_create();

void net_destory(BaseNet *net);

} // namespace jzdl

At this point, having realized that JZDL had been superseded by another inference library called Venus, we decided to look into libvenus.so to determine how it differs. Despite having a relatively similar interface for inference, Venus was designed to use Ingenic’s neural network accelerator chip, which greatly boosts runtime performance, and it would appear that libvenus.so implements a new model serialization format with a vastly different set of layers, as we can see below.

namespace magik {

namespace venus {

class VENUS_API BaseNet {

public:

BaseNet();

virtual ~BaseNet() = 0;

virtual int load_model(const char *model_path, bool memory_model = false, int start_off = 0);

virtual int get_forward_memory_size(size_t &memory_size);

/*memory must be alloced by nmem_memalign, and should be aligned with 64 bytes*/

virtual int set_forward_memory(void *memory);

/*free all memory except for input tensors*/

virtual int free_forward_memory();

/*free memory of input tensors*/

virtual int free_inputs_memory();

virtual void set_profiler_per_frame(bool status = false);

virtual std::unique_ptr<Tensor> get_input(int index);

virtual std::unique_ptr<Tensor> get_input_by_name(std::string &name);

virtual std::vector<std::string> get_input_names();

virtual std::unique_ptr<const Tensor> get_output(int index);

virtual std::unique_ptr<const Tensor> get_output_by_name(std::string &name);

virtual std::vector<std::string> get_output_names();

virtual ChannelLayout get_input_layout_by_name(std::string &name);

virtual int run();

};

}

}

Gaining shell access to the V3 Pro and V4 cameras

Reviewing the logs

After uncovering the differences between the contents of the /tmp/edgeai folder in V3 and V3 Pro, we shifted focus back to the original target of our research, the V3 Pro camera. One of the first things to investigate with our V3 Pro was the camera’s log files. While the logs are intended to assist Wyze’s customer support in troubleshooting issues with a device, they can also provide a wealth of information from a research perspective.

By following the process outlined by Wyze Support, we forced the camera to write encrypted and compressed logs to its SD card, but we didn’t know the encryption type to decrypt them. However, looking deeper into the system binaries, we came across a binary named encrypt, which we suspected may be helpful in figuring out how the logs were encrypted.

We then reversed the ‘encrypt’ binary and found that Wyze uses a hardcoded encryption key, “34t4fsdgdtt54dg2“, with a 0’d out 16 byte IV and AES in CBC mode to encrypt its logs.

Cross-validating with firmware binaries from other cameras, we saw that the key was consistent across the devices we looked at, making them trivial to decrypt. The following script can be used to decrypt and decompress logs into a readable format:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import sys, tarfile, gzip, io

# Constants

KEY = b'34t4fsdgdtt54dg2' # AES key (must be 16, 24, or 32 bytes long)

IV = b'\x00' * 16 # Initialization vector for CBC mode

# Set up the AES cipher object

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, IV)

# Read the encrypted input file

with open(sys.argv[1], 'rb') as infile:

encrypted_data = infile.read()

# Decrypt the data

decrypted_data = cipher.decrypt(encrypted_data)

# Remove padding (PKCS7 padding assumed)

padding_len = decrypted_data[-1]

decrypted_data = decrypted_data[:-padding_len]

# Decompress the tar data in memory

tar_stream = io.BytesIO(decrypted_data)

with tarfile.open(fileobj=tar_stream, mode='r') as tar:

# Extract the first gzip file found in the tar archive

for member in tar.getmembers():

if member.isfile() and member.name.endswith('.gz'):

gz_file = tar.extractfile(member)

gz_data = gz_file.read()

break

# Decompress the gzip data in memory

gz_stream = io.BytesIO(gz_data)

with gzip.open(gz_stream, 'rb') as gzfile:

extracted_data = gzfile.read()

# Write the extracted data to a log file

with open('log', 'wb') as f:

f.write(extracted_data)

Command injection vulnerability in V3 Pro

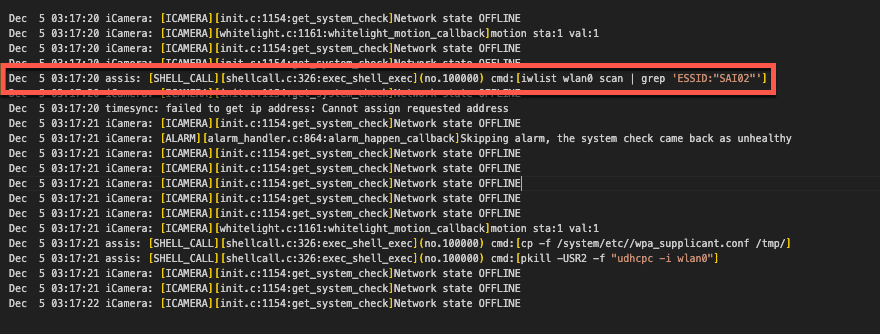

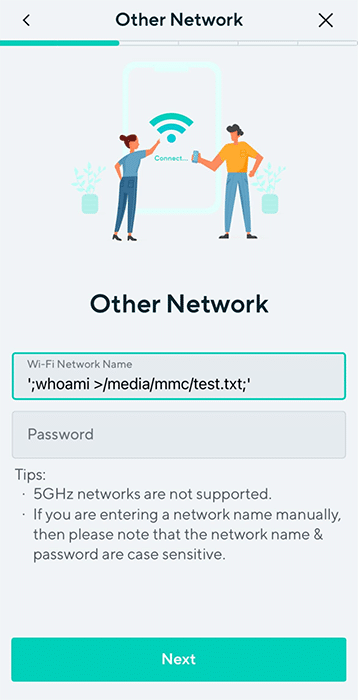

Our initial review of the decrypted logs identified several interesting “SHELL_CALL” entries that detailed commands spawned by the camera. One, in particular, caught our attention, as the command spawned contained a user-specified SSID:

We traced this command back to the /system/lib/libwyzeUtilsPlatform.so library, where the net_service_thread function calls it. The net_service_thread function is ultimately invoked by /system/bin/iCamera during the camera setup process, where its purpose is to initialize the camera’s wireless networking.

Further review of this function revealed that the command spawned through SHELL_CALL was crafted through a format string that used the camera’s SSID without sanitization.

00004604 snprintf(&str, 0x3fb, "iwlist wlan0 scan | grep \'ESSID:\"%s\"\'", 0x18054, var_938, var_934, var_930, err_21, var_928);

00004618 int32_t $v0_6 = exec_shell_sync(&str, &var_918);We had a strong suspicion that we could gain code execution by passing the camera a specially crafted SSID with a properly escaped command. All that was left now was to test our theory.

Placing the camera in setup mode, we used the mobile Wyze app to configure an SSID containing a command we wanted to execute, “whoami > /media/mmc/test.txt”, and scanned the QR code with our camera. We then checked the camera’s SD card and found a newly created test.txt file confirming we had command execution as root. Success!

However, Wyze patched this vulnerability in January 2024 before we could report it. Still, since we didn’t update our camera firmware, we could use the vulnerability to root and continue exploring the device.

Getting shell access on the Wyze Cam V3 Pro

Command execution meant progress, but we couldn’t stop there. We ideally needed a remote shell to continue our research effectively, although we had the following limitations:

- The Wyze app only allows you to use SSIDs that are 32 characters or less. You can get around this by manually generating a QR code. However, the camera still has limitations on the length of the SSID.

- The command injection prevents the camera from connecting to a WiFi network.

We circumvented these obstacles by creating a script on the camera’s SD card, which allowed us to spawn additional commands without size constraints. The wpa_supplicant binary, already on the camera’s filesystem, could then be used to set up networking manually and spawn a Dropbear SSH server that we had compiled and placed on the SD card for shell access (more on this later).

#!/bin/sh

#clear old logs

rm /media/mmc/*.txt

#Setup networking

/sbin/ifconfig wlan0 up

/system/bin/wpa_supplicant -D nl80211 -iwlan0 -c /media/mmc/wpa.conf -B

/sbin/udhcpc -i wlan0

#Spawn Droopbear SSH server

chmod +x /media/mmc/dropbear

chmod 600 /media/mmc/dropbear_key

nohup /media/mmc/dropbear -E -F -p 22 -r /media/mmc/dropbear_key 1>/media/mmc/stdout.txt 2>/media/mmc/stderr.txt &We could now SSH into the device, giving us shell access as root.

Wyze Cam V4: A new challenge

While we were investigating the V3 Pro, Wyze released a new camera (Wyze Cam V4) (in March 2024), and in the spirit of completeness, we decided to give it a poke as well. However, there was a problem: the device was so new that the Wyze support site had no firmware available for download.

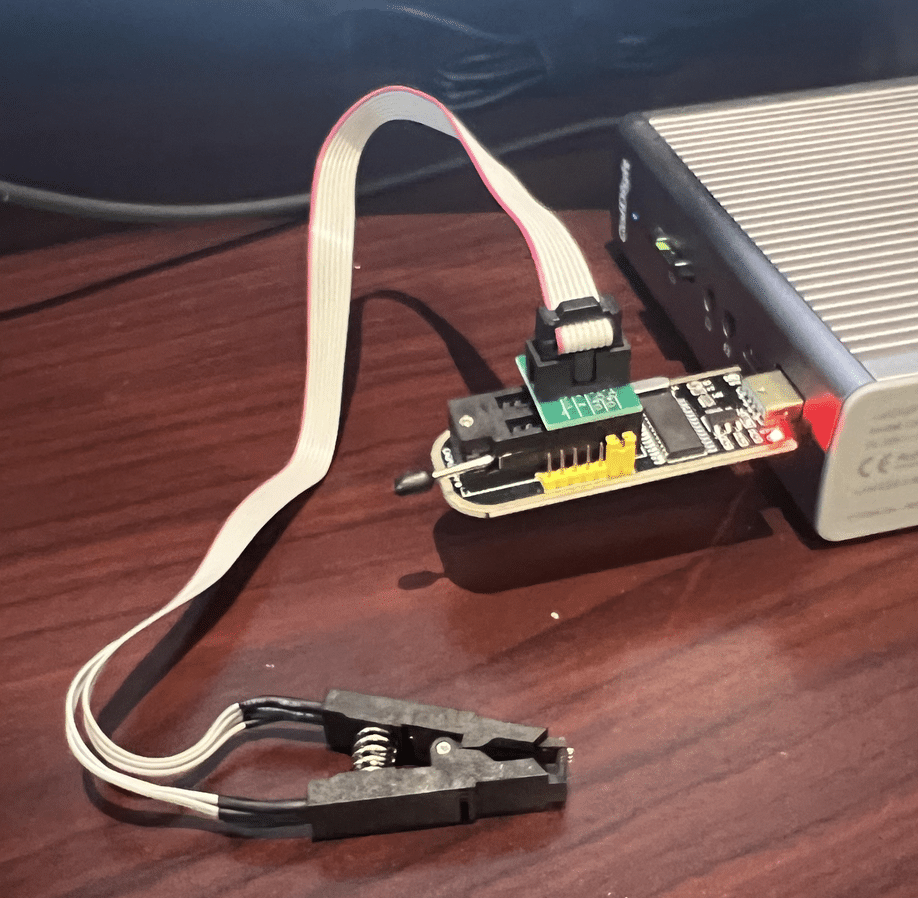

This meant we had to look towards other options for obtaining the firmware and opted for the more tactile method of chip-off extraction.

Extracting firmware from the Flash

While chip-off extraction can sometimes be complicated, it is relatively straightforward if you have the appropriate clips or test sockets and a compatible chip reader that supports the flash memory you are targeting.

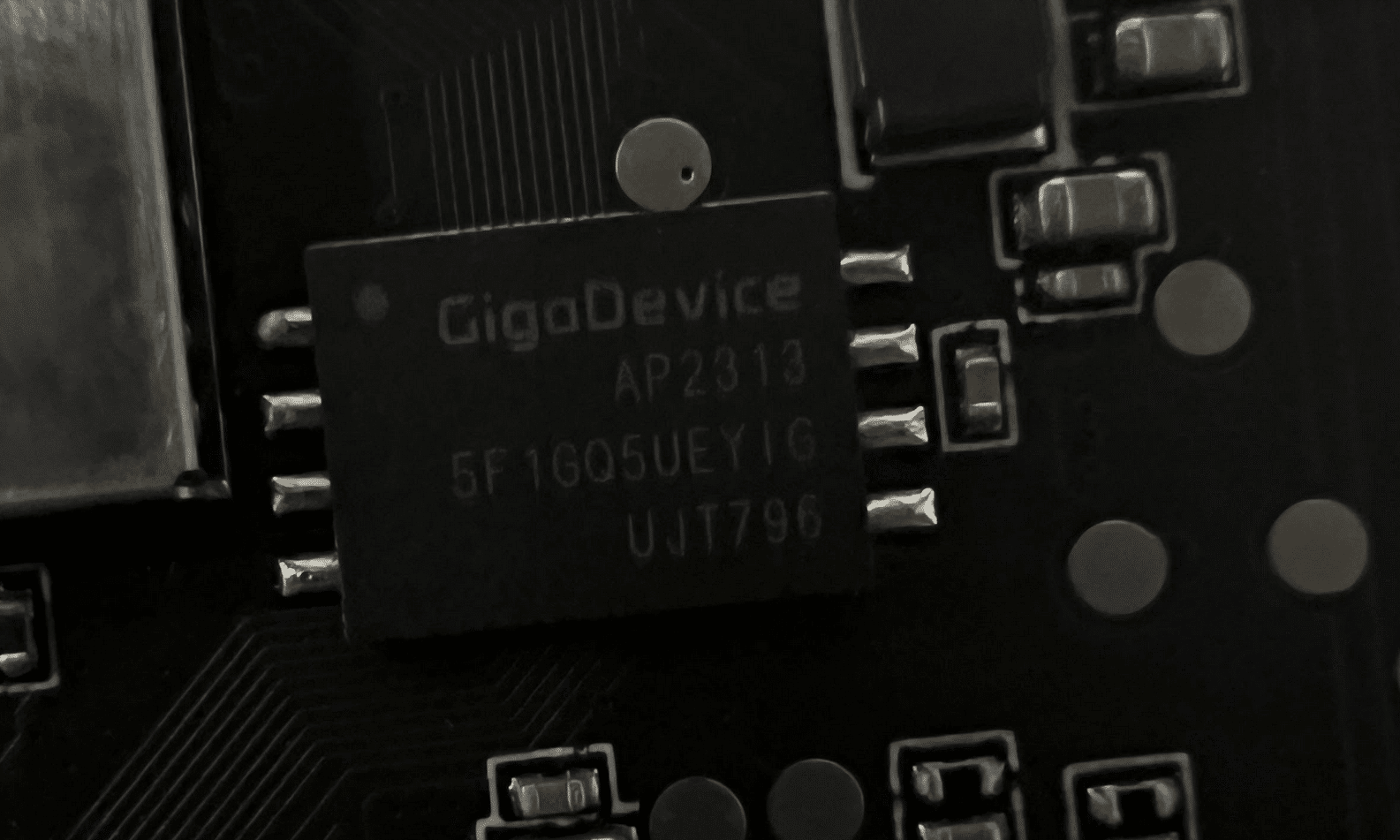

Since we had several V3 Pros and only one Cam V4, we first attempted this process with our more well-stocked companion – the V3 Pro. We carefully disassembled the camera and desoldered the flash memory, which was SPI NAND flash from GIGADEVICE.

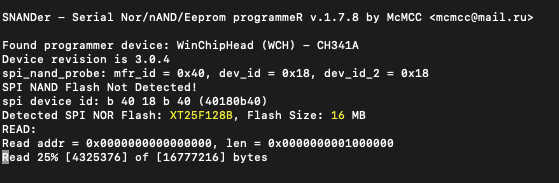

Now, all we needed was a way to read it. We searched GitHub for the chip’s part number (GD5F1GQ5UE) and found a flash memory program called SNANDer that supported it. We then used SNANDer, a CH341A programmer, to extract the firmware.

We repeated the same process with the Cam V4. Unlike the previous camera, this one used SPI NOR Flash from a company called XTX, which was not a problem as, fortunately, SNANDer worked yet again.

Wyze Cam V3 Pro – “algos”

A triage of the firmware we had previously dumped from the Wyze Cam V3 Pro’s flash memory showed that it contained an “algos” partition that wasn’t present in the firmware we downloaded from the support site.

This partition contained several model files:

- facecap_att.bin

- facecap_blur.bin

- facecap_det.bin

- passengerfs_det.bin

- personvehicle_det.bin

- Platedet.bin

However, after further investigation, we concluded that the camera wasn’t actively using these models for detection. We found no references to these models in the binaries we pulled from the camera. In a test to see if these models were necessary, we deleted them from the device, and the camera continued to function normally, confirming that they were not essential to its operation. Additionally, unlike Edge AI, sinker did not attempt to download these models again.

Upgrading the Vulnerability to V4

Now that we had firmware available for the Wyze Cam V4, we began combing through it, looking for possible vulnerabilities. To our astonishment, the “libwyzeUtilsPlatform.so” command injection vulnerability patched in the V3 Pro was reintroduced in the Wyze Cam V4.

Exploiting this vulnerability to gain root access to the V4 was almost identical to the process we used in the V3 Pro. However, the V4 uses Bluetooth instead of a QR code to configure the camera.

We reported this vulnerability to Wyze, which was later patched in firmware version 4.52.7.0367. Our security advisory on CVE-2024-37066 provides a more in-depth analysis of this vulnerability.

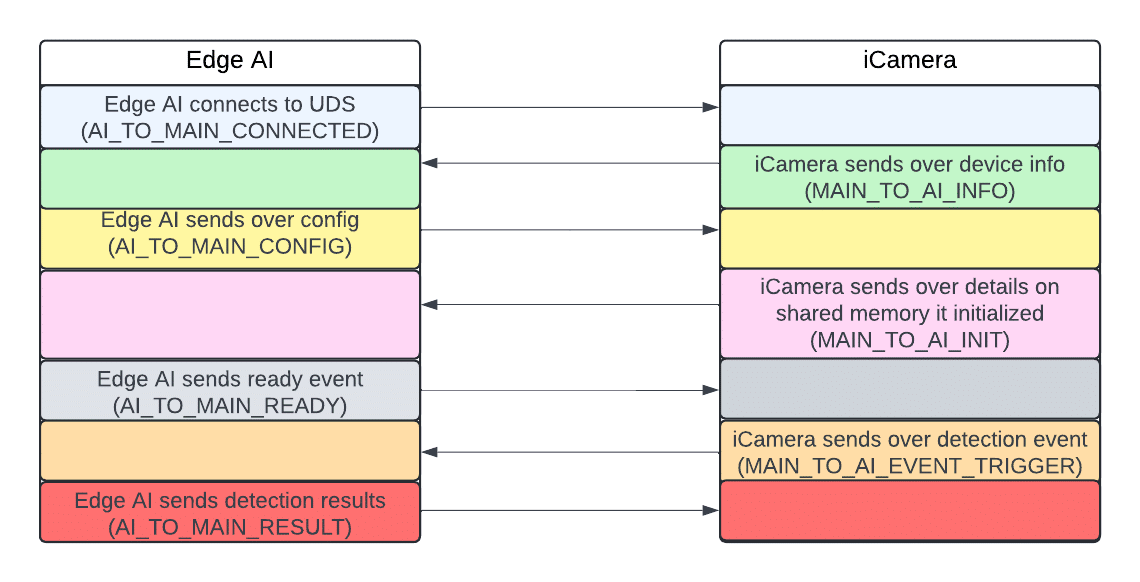

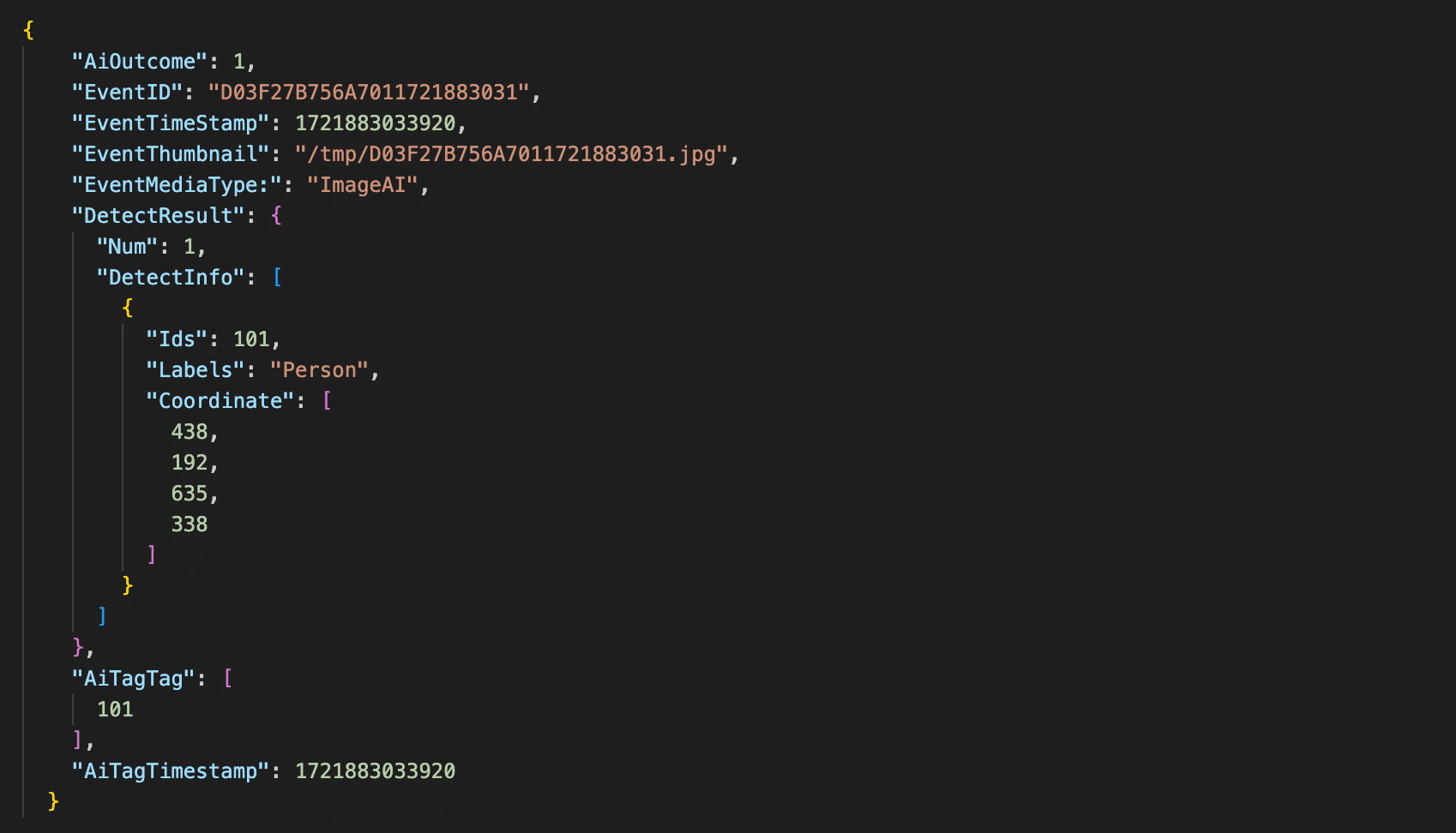

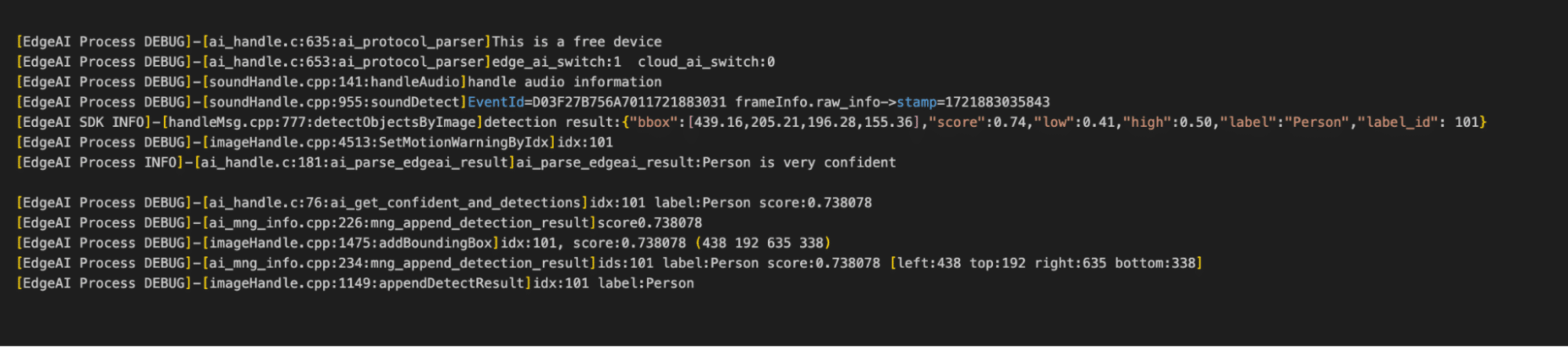

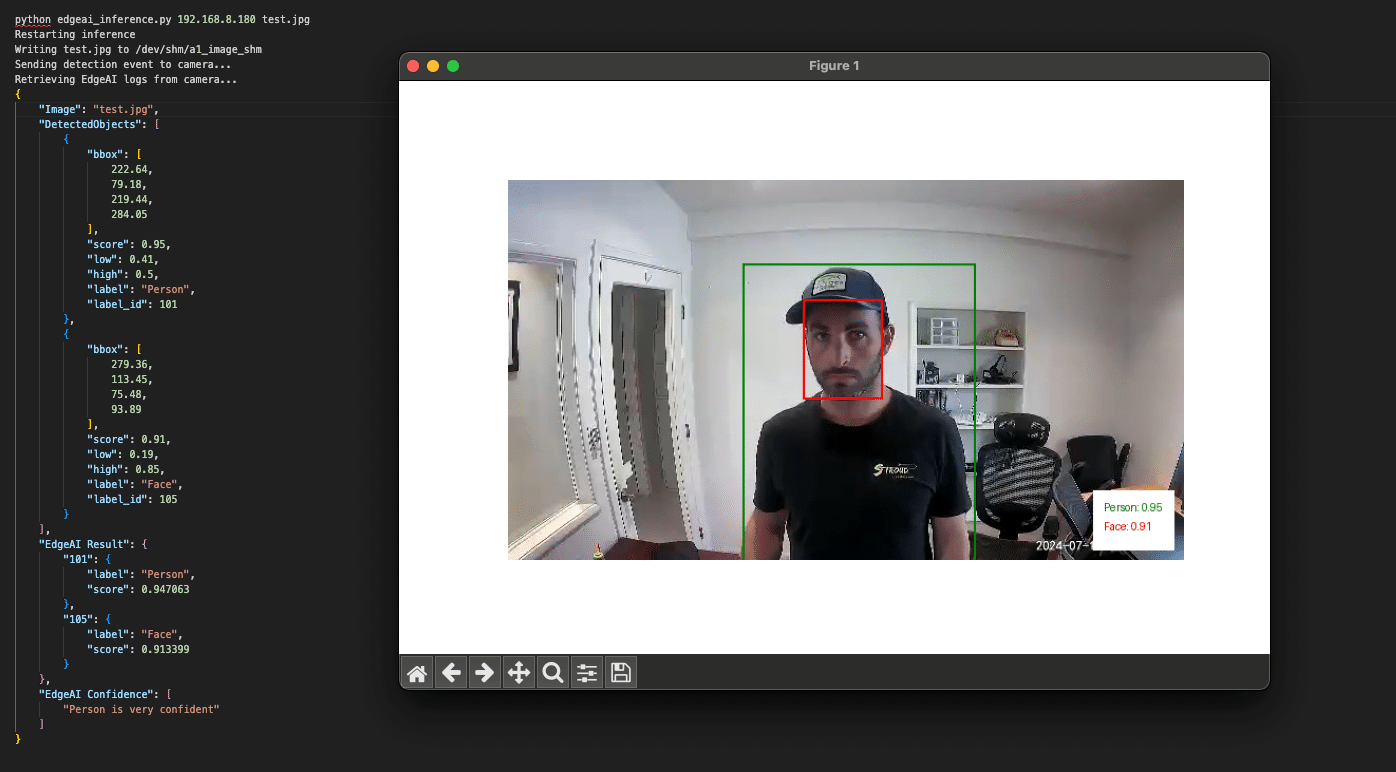

Attacking the Inference Process

Some Online Sleuthing

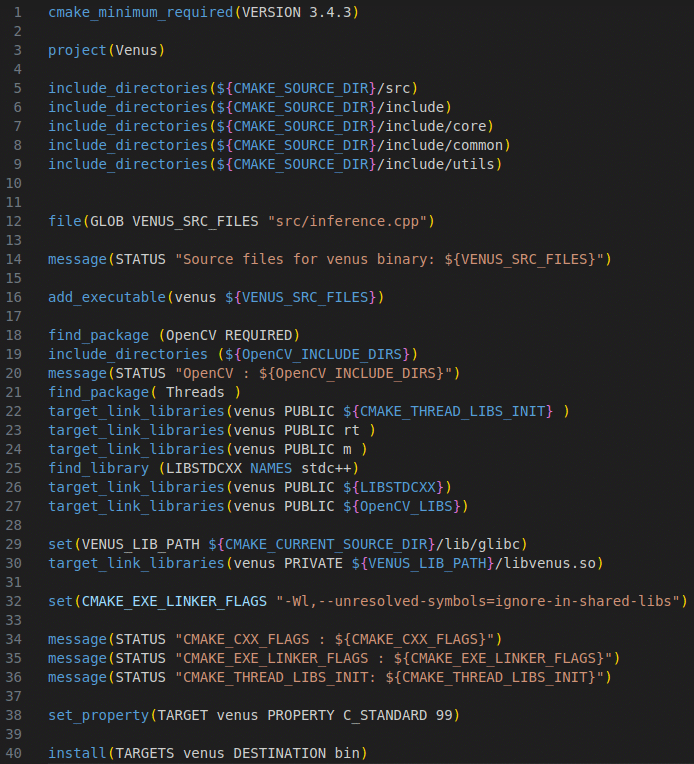

While investigating how best to load the inference libraries on the device, we came across a GitHub repository containing several SDKs for various versions of the JZDL and Venus libraries. The repository is a treasure trove of header files, libraries, models, and even conversion tools to convert models in popular formats such as PyTorch, ONNX, and TensorFlow to the proprietary Ingenic/Magik format. However, to use these libraries, we’d need a bespoke build system.

Buildroot: The Box of Horrors

The first attempt at attacking the inference process relied on trying to compile a simple program to load libvenus.so and perform inference on an image. In the Ingenic Magik toolkit repository, we found a lovely example program written in C++ that used the Venus library to perform inference and generate bounding boxes around detections. Perfect! Now, all we need is a cross-platform build chain to compile it.

Thankfully, it’s simple to configure a build system using Buildroot, an open-source tool designed for compiling custom embedded Linux systems. We opted to use Buildroot version 2022.05, and used the following configuration for compilation based on the wz_mini_hacks documentation:

Stay Ahead of AI Security Risks

Get research-driven insights, emerging threat analysis, and practical guidance on securing AI systems—delivered to your inbox.