Learn from our AI Security Experts

Discover every model. Secure every workflow. Prevent AI attacks - without slowing innovation.

min read

Integrating HiddenLayer’s Model Scanner with Databricks Unity Catalog

As machine learning becomes more embedded in enterprise workflows, model security is no longer optional. From training to deployment, organizations need a streamlined way to detect and respond to threats that might lurk inside their models. The integration between HiddenLayer’s Model Scanner and Databricks Unity Catalog provides an automated, frictionless way to monitor models for vulnerabilities as soon as they are registered. This approach ensures continuous protection without slowing down your teams.

Introduction

As machine learning becomes more embedded in enterprise workflows, model security is no longer optional. From training to deployment, organizations need a streamlined way to detect and respond to threats that might lurk inside their models. The integration between HiddenLayer’s Model Scanner and Databricks Unity Catalog provides an automated, frictionless way to monitor models for vulnerabilities as soon as they are registered. This approach ensures continuous protection without slowing down your teams.

In this blog, we’ll walk through how this integration works, how to set it up in your Databricks environment, and how it fits naturally into your existing machine learning workflows.

Why You Need Automated Model Security

Modern machine learning models are valuable assets. They also present new opportunities for attackers. Whether you are deploying in finance, healthcare, or any data-intensive industry, models can be compromised with embedded threats or exploited during runtime. In many organizations, models move quickly from development to production, often with limited or no security inspection.

This challenge is addressed through HiddenLayer’s integration with Unity Catalog, which automatically scans every new model version as it is registered. The process is fully embedded into your workflow, so data scientists can continue building and registering models as usual. This ensures consistent coverage across the entire lifecycle without requiring process changes or manual security reviews.

This means data scientists can focus on training and refining models without having to manually initiate security checks or worry about vulnerabilities slipping through the cracks. Security engineers benefit from automated scans that are run in the background, ensuring that any issues are detected early, all while maintaining the efficiency and speed of the machine learning development process. HiddenLayer’s integration with Unity Catalog makes model security an integral part of the workflow, reducing the overhead for teams and helping them maintain a safe, reliable model registry without added complexity or disruption.

Getting Started: How the Integration Works

To install the integration, contact your HiddenLayer representative to obtain a license and access the installer. Once you’ve downloaded and unzipped the installer for your operating system, you’ll be guided through the deployment process and prompted to enter environment variables.

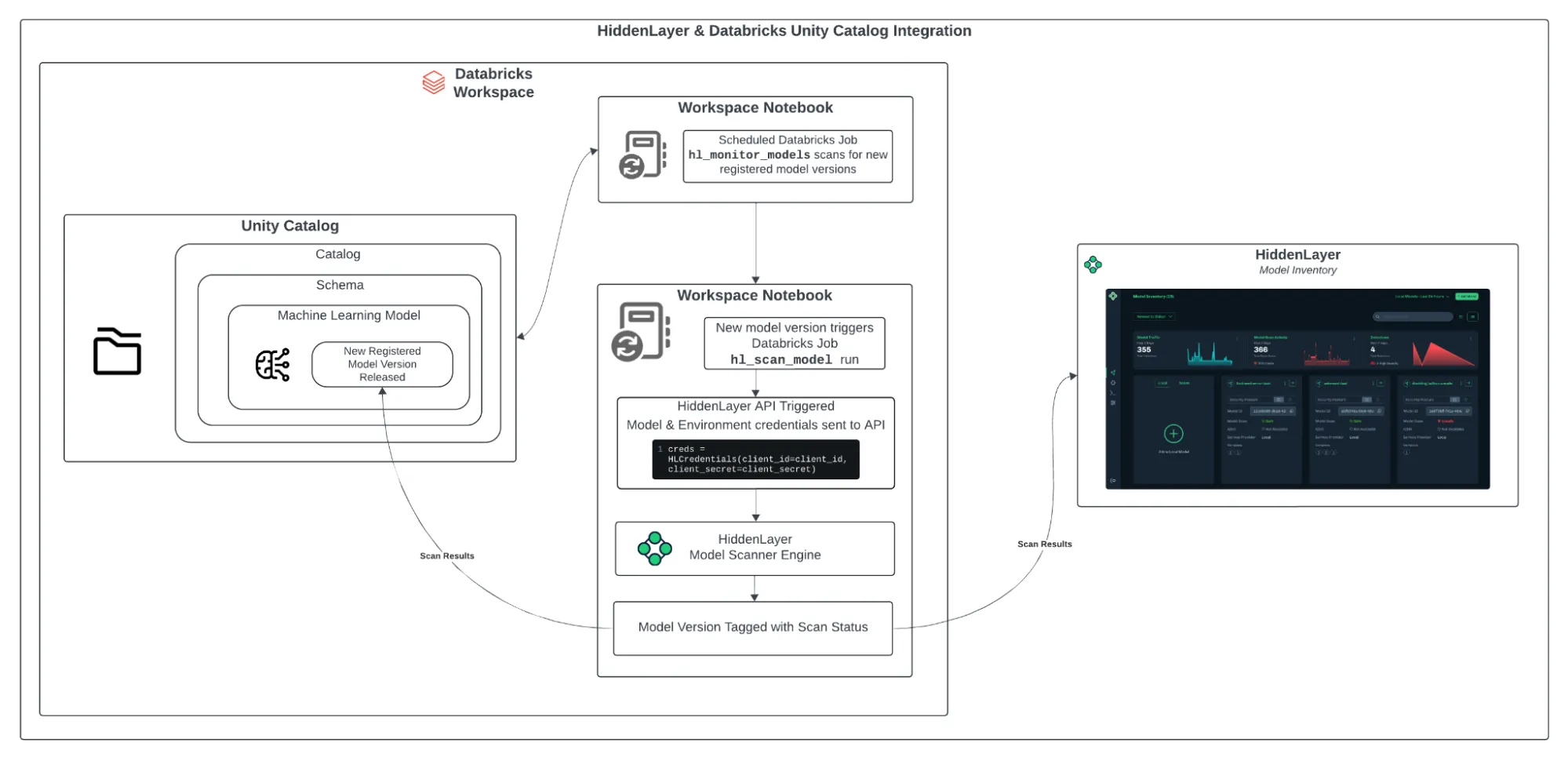

Once installed, this integration monitors your Unity Catalog for new model versions and automatically sends them to HiddenLayer’s Model Scanner for analysis. Scan results are recorded directly in Unity Catalog and the HiddenLayer console, allowing both security and data science teams to access the information quickly and efficiently.

Figure 1: HiddenLayer & Databricks Architecture Diagram

The integration is simple to set up and operates smoothly within your Databricks workspace. Here’s how it works:

- Install the HiddenLayer CLI: The first step is to install the HiddenLayer CLI on your system. Running this installation will set up the necessary Python notebooks in your Databricks workspace, where the HiddenLayer Model Scanner will run.

- Configure the Unity Catalog Schema: During the installation, you will specify the catalogs and schemas that will be used for model scanning. Once configured, the integration will automatically scan new versions of models registered in those schemas.

- Automated Scanning: A monitoring notebook called hl_monitor_models runs on a scheduled basis. It checks for newly registered model versions in the configured schemas. If a new version is found, another notebook, hl_scan_model, sends the model to HiddenLayer for scanning.

- Reviewing Scan Results After scanning, the results are added to Unity Catalog as model tags. These tags include the scan status (pending, done, or failed) and a threat level (safe, low, medium, high, or critical). The full detection report is also accessible in the HiddenLayer Console. This allows teams to evaluate risk without needing to switch between systems.

Why This Workflow Works

This integration helps your team stay secure while maintaining the speed and flexibility of modern machine learning development.

- No Process Changes for Data Scientists

Teams continue working as usual. Model security is handled in the background. - Real-Time Security Coverage

Every new model version is scanned automatically, providing continuous protection. - Centralized Visibility

Scan results are stored directly in Unity Catalog and attached to each model version, making them easy to access, track, and audit. - Seamless CI/CD Compatibility

The system aligns with existing automation and governance workflows.

Final Thoughts

Model security should be a core part of your machine learning operations. By integrating HiddenLayer’s Model Scanner with Databricks Unity Catalog, you gain a secure, automated process that protects your models from potential threats.

This approach improves governance, reduces risk, and allows your data science teams to keep working without interruptions. Whether you’re new to HiddenLayer or already a user, this integration with Databricks Unity Catalog is a valuable addition to your machine learning pipeline. Get started today and enhance the security of your ML models with ease.

All Resources

MITRE ATLAS: The Intersection of Cybersecurity and AI

At HiddenLayer, we publish a lot of technical research about Adversarial Machine Learning. It’s what we do. But unless you are constantly at the bleeding edge of cybersecurity threat research and artificial intelligence, like our SAI Team, it can be overwhelming to understand how urgent and important this new threat vector can be to your organization. Thankfully, MITRE has focused its attention towards educating the general public about Adversarial Machine Learning and security for AI systems.

Introduction

At HiddenLayer, we publish a lot of technical research about Adversarial Machine Learning. It’s what we do. But unless you are constantly at the bleeding edge of cybersecurity threat research and artificial intelligence, like our SAI Team, it can be overwhelming to understand how urgent and important this new threat vector can be to your organization. Thankfully, MITRE has focused its attention towards educating the general public about Adversarial Machine Learning and security for AI systems.

Who is MITRE?

For those in cybersecurity, the name MITRE is well-known throughout the industry. For our Data Scientist readers and other non-cybersecurity professionals who may be less familiar, MITRE is a not-for-profit research and development organization sponsored by the US government and private companies within cybersecurity and many other industries.

Some of the most notable projects MITRE maintains within cybersecurity:

- The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) program identifies and tracks software vulnerabilities and is leveraged by Vulnerability Management products

- The MITRE ATT&CK (Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge) framework describes the various stages of traditional endpoint attack tactics and techniques and is leveraged by Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) products

MITRE is now focusing its efforts on helping the world navigate the landscape of threats to machine learning systems.

“Ensuring the safety and security of consequential ML-enabled systems is crucial if we want ML to help us solve internationally critical challenges. With ATLAS, MITRE is building on our historical strength in cybersecurity to empower security professionals and ML engineers as they take on the new wave of security threats created by the unique attack surfaces of ML-enabled systems,” says Dr. Christina Liaghati, AI Strategy Execution Manager, MITRE Labs.

What is MITRE ATLAS?

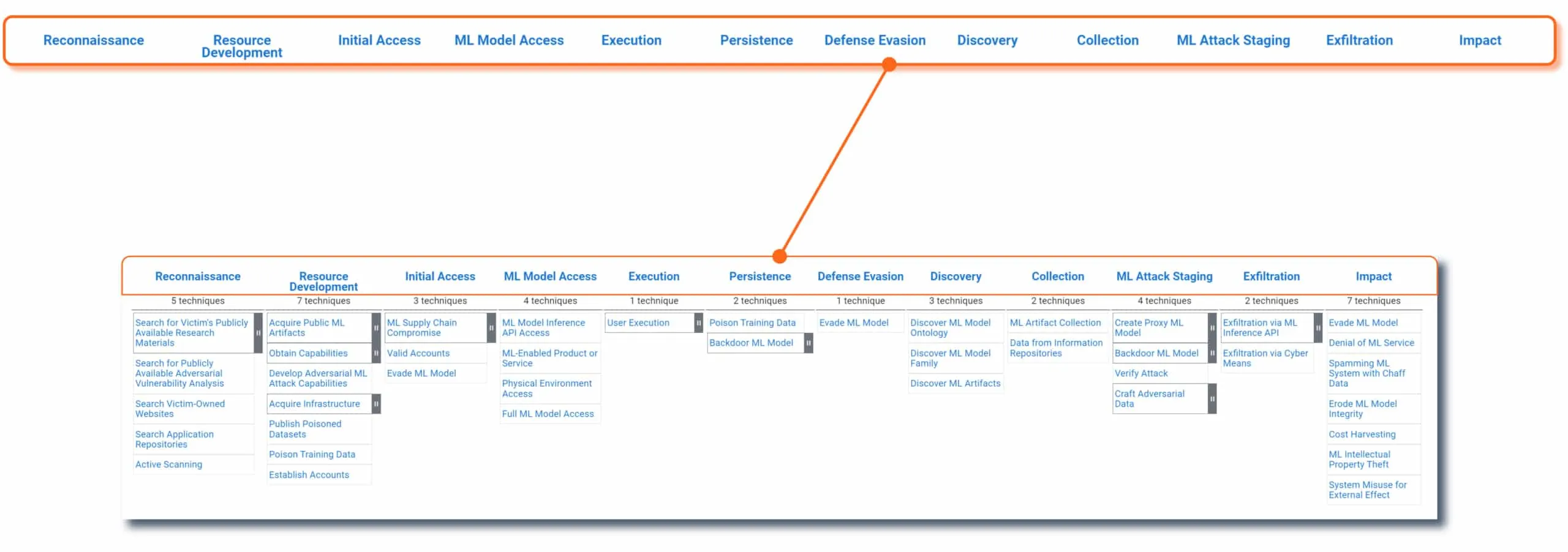

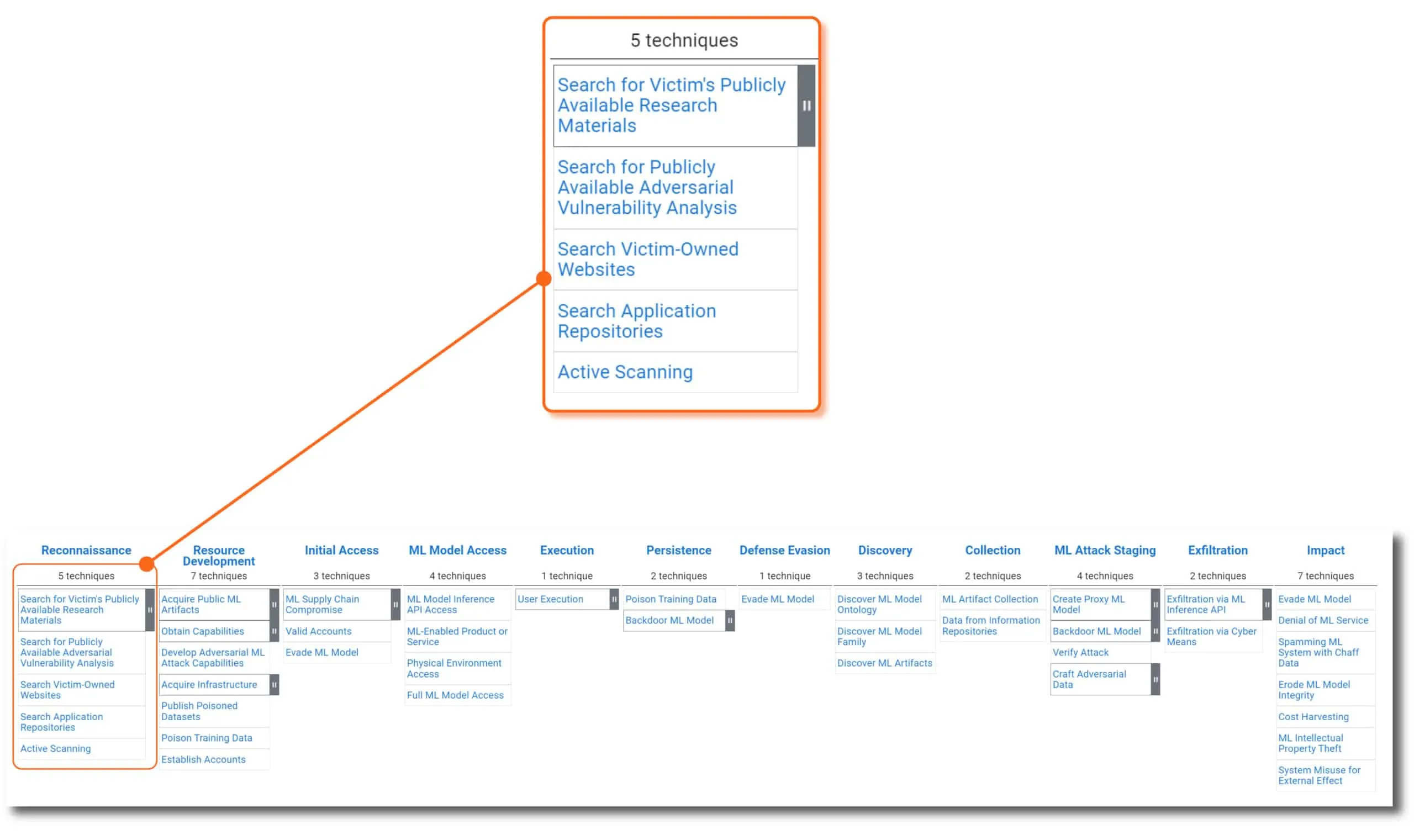

First released in June 2021, MITRE ATLAS stands for “Adversarial Threat Landscape for Artificial-Intelligence Systems.” It is a knowledge base of adversarial machine learning tactics, techniques, and case studies designed to help cybersecurity professionals, data scientists, and their companies stay up to date on the latest attacks and defenses against adversarial machine learning. The ATLAS matrix is modelled after the well-known MITRE ATT&CK framework.

https://youtu.be/3FN9v-y-C-w

Tactics (Why)

The column headers of the ATLAS matrix are the adversary’s motivations. In other words, “why” they are trying to conduct the attack. Going from left to right, this is the likely sequence an attacker will implement throughout the lifespan of an ML-targeted attack. Each tactic is assigned a unique ATLAS ID with the prefix “TA” - for example, the Reconnaissance tactic ID is AML.TA0002 .

Techniques (How)

Beneath each tactic is a list of techniques (and sub-techniques) an adversary could use to carry out their objective. The techniques convey “how” an attacker will carry out their tactical objective. The list of techniques will continue to grow as new attacks are developed by adversaries and discovered in the wild by threat researchers like HiddenLayer’s SAI Team and others within the industry. Each technique is assigned a unique ATLAS ID with the prefix “T” - for example, ML Model Inference API Access is AML.T0040.

Case Studies (Who)

Within the details of each MITRE ATLAS technique, you will find links to a number of real-world and academic examples of the techniques discovered in the wild. Individual case studies tell us “who” have been victims of an attack and are mapped to various techniques observed within the full scope of the attack. Each case study is assigned a unique ATLAS ID with the prefix “CS” - for example, the case study ID for Bypassing Cylance’s AI Malware Detection is AML.CS0003.

In this real-world case study, Cylance was a cybersecurity company that developed a malware detection technology that used machine learning models trained on known malware and clean files to detect new zero-day malware and avoid false positives. This adversarial machine learning attack was executed utilizing a number of ATLAS tactics and techniques to infer the features and decision-making in the Cylance ML Model and devised an adversarial attack by appending strings from clean files to known malware files to avoid detection. The researchers used the following tactics and techniques to carry out the full attack, successfully bypassing the Cylance malware detection ML Models by modifying malware previously detected to be categorized as benign.

[wpdatatable id=4]

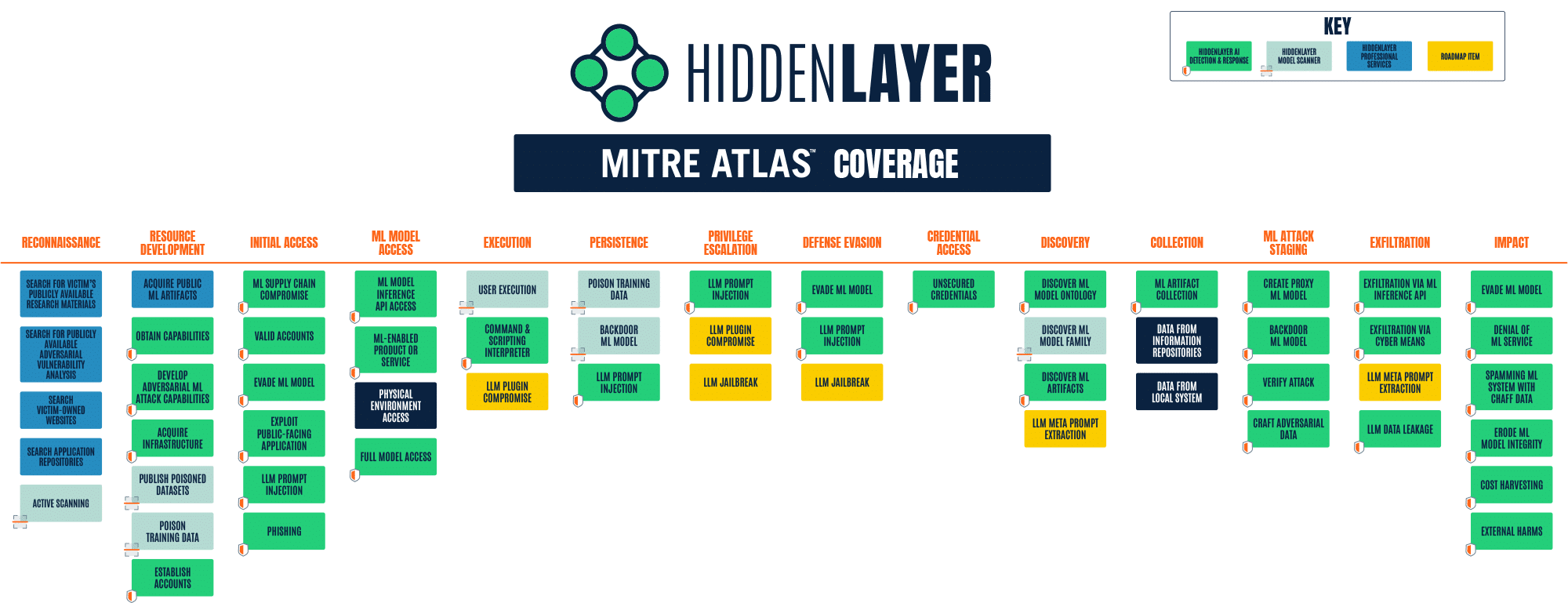

How HiddenLayer Covers MITRE ATLAS

HiddenLayer’s MLSec Platform and services have been designed and developed with MITRE ATLAS in mind from their inception. The product and services matrix below highlights which HiddenLayer solution effectively protects against the different ATLAS attacks.

HiddenLayer MLDR (Machine Learning Detection & Response) is our cybersecurity solution that monitors, detects, and responds to Adversarial Machine Learning attacks targeted at ML Models. Our patent-pending technology provides a non-invasive, software-based platform that monitors the inputs and outputs of your machine learning algorithms for anomalous activity consistent with adversarial ML attack techniques.

MLDR’s detections are mapped to ATLAS tactic IDs to help security operations and data scientists understand the possible motives, current stage, and likely next stage of the attack. They are also mapped to ATLAS technique IDs, providing context to better understand the active threat and determine the most appropriate response to protect against it.

Conclusion

If there is one universal truth about cybersecurity threat actors, they do not stay in their presumptive lanes. They will exploit any vulnerability, utilize any method, and enter through any opening to get to their ill-gotten gains. Although ATLAS focuses on adversarial machine learning and ATT&CK focuses on traditional endpoint attacks, machine learning models are developed within corporate networks running traditional endpoints and cloud platforms. “AI on the Edge” allows the general public to interface with them. As such, machine learning models need to be audited, red team tested, hardened, protected, and defended with similar oversight as traditional endpoints.

Here are just a few recent examples of ML Models introducing new cybersecurity risk and threats to IT organizations:

- ML Models can be a launchpad for malware. HiddenLayer’s SAI Research Team published research on how ML models can be weaponized with ransomware.

- Code suggestion AI can be exploited as a supply-chain attack. Training data is vulnerable to poison attacks, suggesting code to developers who could inadvertently insert malicious code into a company’s software.

- Open-source ML Models can be an entry point for malware. Dubbed “Pickle Strike,” HiddenLayer’s SAI Research Team discovered a number of malicious pickle files within VirusTotal. Pickle files are a common file format for ML Models.

For CIO/CISOs, Security Operations, and Incident Responders, we’ve been down this road before. New tech stacks mean new attack and defense methods. The rapid adoption of AI is very similar to the adoption of mobile, cloud, container, IOT, etc. into the business and IT world. MITRE ATLAS helps fast-track our understanding of ML adversaries and their tactics and techniques so we can devise defenses and responses to those attacks.

For CDOs and Data Science teams, the threats and attacks on your ML models and intellectual property could make your jobs more difficult and be an annoying distraction to your goal of developing newer better generations of your ML Models. MITRE ATLAS acts as a knowledge base and comprehensive inventory of weaknesses in our ML models that could be exploited by adversaries allowing us to proactively secure our models during development and for monitoring in production.

MITRE ATLAS bridges the gap between both the cybersecurity and data science worlds. Its framework gives us a common language to discuss and devise a strategy to protect and preserve our unique AI competitive advantage.

Safeguarding AI with AI Detection and Response

In previous articles, we’ve discussed the ubiquity of AI-based systems and the risks they’re facing; we’ve also described the common types of attacks against machine learning (ML) and built a list of adversarial ML tools and frameworks that are publicly available. Today, the time has come to talk about countermeasures.

In previous articles, we’ve discussed the ubiquity of AI-based systems and the risks they’re facing; we’ve also described the common types of attacks against machine learning (ML) and built a list of adversarial ML tools and frameworks that are publicly available. Today, the time has come to talk about countermeasures.

Over the past year, we’ve been working on something that fundamentally changes how we approach the security of ML and AI systems. Typically undertaken is a robustness-first approach which adds complexity to models, often at the expense of performance, efficacy, and training cost. To us, it felt like kicking the can down the road and not addressing the core problem - that ML is under attack.

Once upon a time…

Back in 2019, the future founders of HiddenLayer worked closely together at a next-generation antivirus company. Machine learning was at the core of their flagship endpoint product, which was making waves and disrupting the AV industry. As fate would have it, the company suffered an attack where an adversary had created a universal bypass against the endpoint malware classification model. This meant that the attacker could alter a piece of malware in such a way that it would make anything from a credential stealer to ransomware appear benign and authoritatively safe.

The ramifications of this were serious, and our team scrambled to assess the impact and provide remediation. In dealing with the attack, we realized that this problem was indeed much bigger than the AV industry itself and bigger still than cybersecurity - attacks like these were going to affect almost every vertical. Having had to assess, remediate and defend against future attacks, we realized we were uniquely suited to help address this growing problem.

In a few years’ time, we went on to form HiddenLayer, and with that - our flagship product, Machine Learning Detection and Response, or MLDR.

What is MLDR?

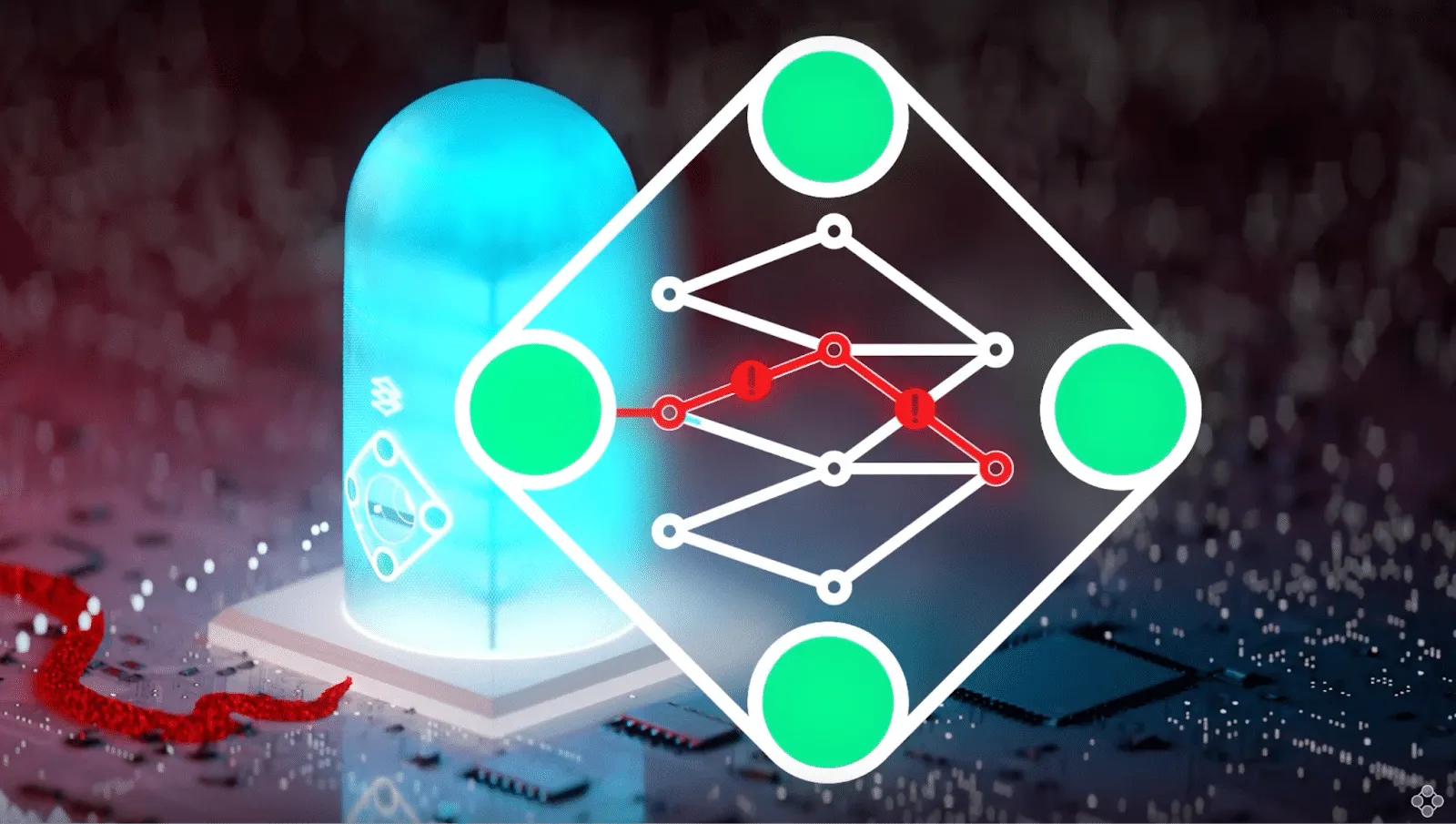

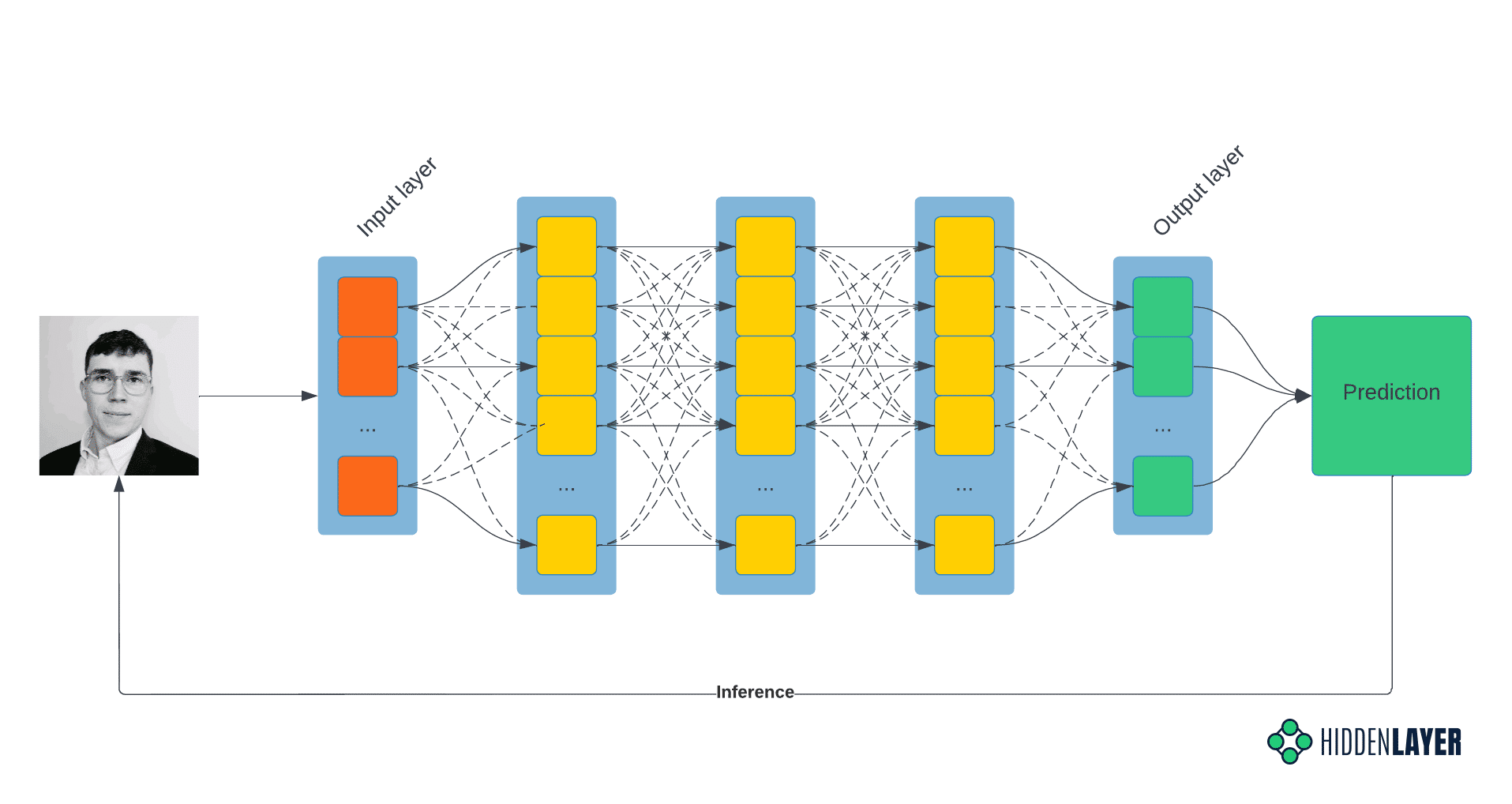

Figure 1: An artist’s impression of MLDR in action - a still from the HiddenLayer promotional video

Platforms such as Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR), Extended Detection and Response (XDR), or Managed Detection and Response (MDR) have been widely used to detect and prevent attacks on endpoint devices, servers, and cloud-based resources. In a similar spirit, Machine Learning Detection and Response aims to identify and prevent attacks against machine learning systems. While EDR monitors system and network telemetry on the endpoint, MLDR monitors the inputs and outputs of machine learning models, i.e., the requests that are sent to the model, together with the corresponding model predictions. By analyzing the traffic for any malicious, suspicious, or simply anomalous activity, MLDR can detect an attack at a very early stage and offers ways to respond to it.

Why MLDR & Why Now?

As things stand today, machine learning systems are largely unprotected. We deploy models with the hope that no one will spend the time to find ways to bypass the model, coerce it into adverse behavior or steal it entirely. With more and more adversarial open-source tooling entering the public domain, attacking ML has become easier than ever. If you use ML within your company, perhaps it is a good time to ask yourself a tough question: could you even tell if you were under attack?

The current status quo in ML security is model robustness, where models are made more complex to resist simpler attacks and deter attackers. But this approach has a number of significant drawbacks, such as reduced efficacy, slower performance, and increased retraining costs. Throughout the sector, it is known that security through obscurity is a losing battle, but how about security through visibility instead?

Being able to detect suspicious and anomalous behaviors amongst regular requests to the ML model is extremely important for the model’s security, as most attacks against ML systems start with such anomalous traffic. Once an attack is detected and stakeholders alerted, actions can be taken to block it or prevent it from happening in the future.

With MLDR, we not only enable you to detect attacks on your ML system early on, but we also help you to respond to such attacks, making life even more difficult for adversaries - or cutting them off entirely!

Our Solution

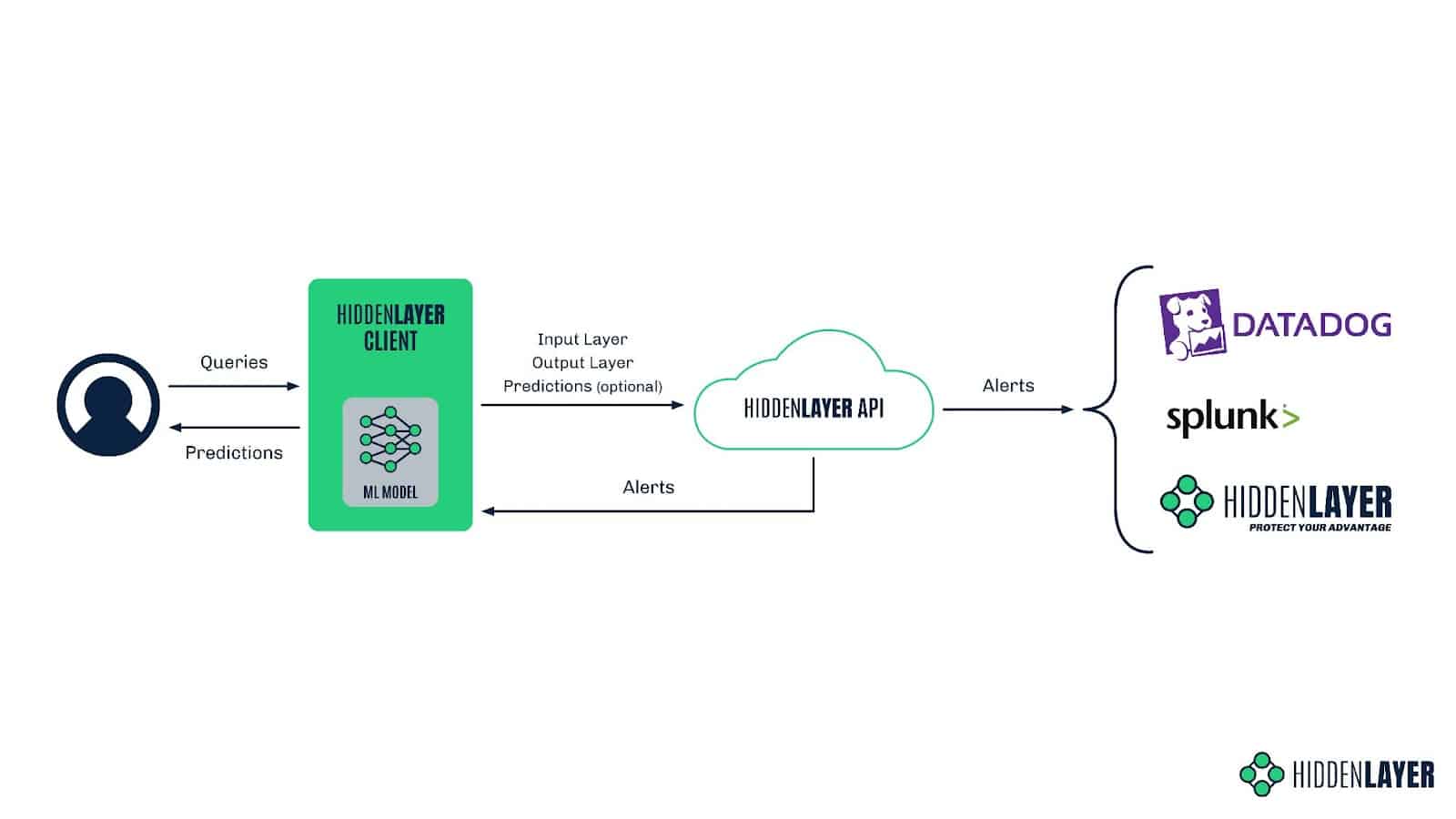

Broadly speaking, our MLDR product comprises two parts: the locally installed client and the cloud-based sensor the client communicates with through an API. The client is installed in the customer’s environment and can be easily implemented around any ML model to start protecting it straight away. It is responsible for sending input vectors from all model queries, together with the corresponding predictions, to the HiddenLayer API. This data is then processed and analyzed for malicious or suspicious activity. If any signs of such activity are detected, alerts are sent back to the customer in a chosen way, be it via Splunk, DataDog, the HiddenLayer UI, or simply a customer-side command-line script.

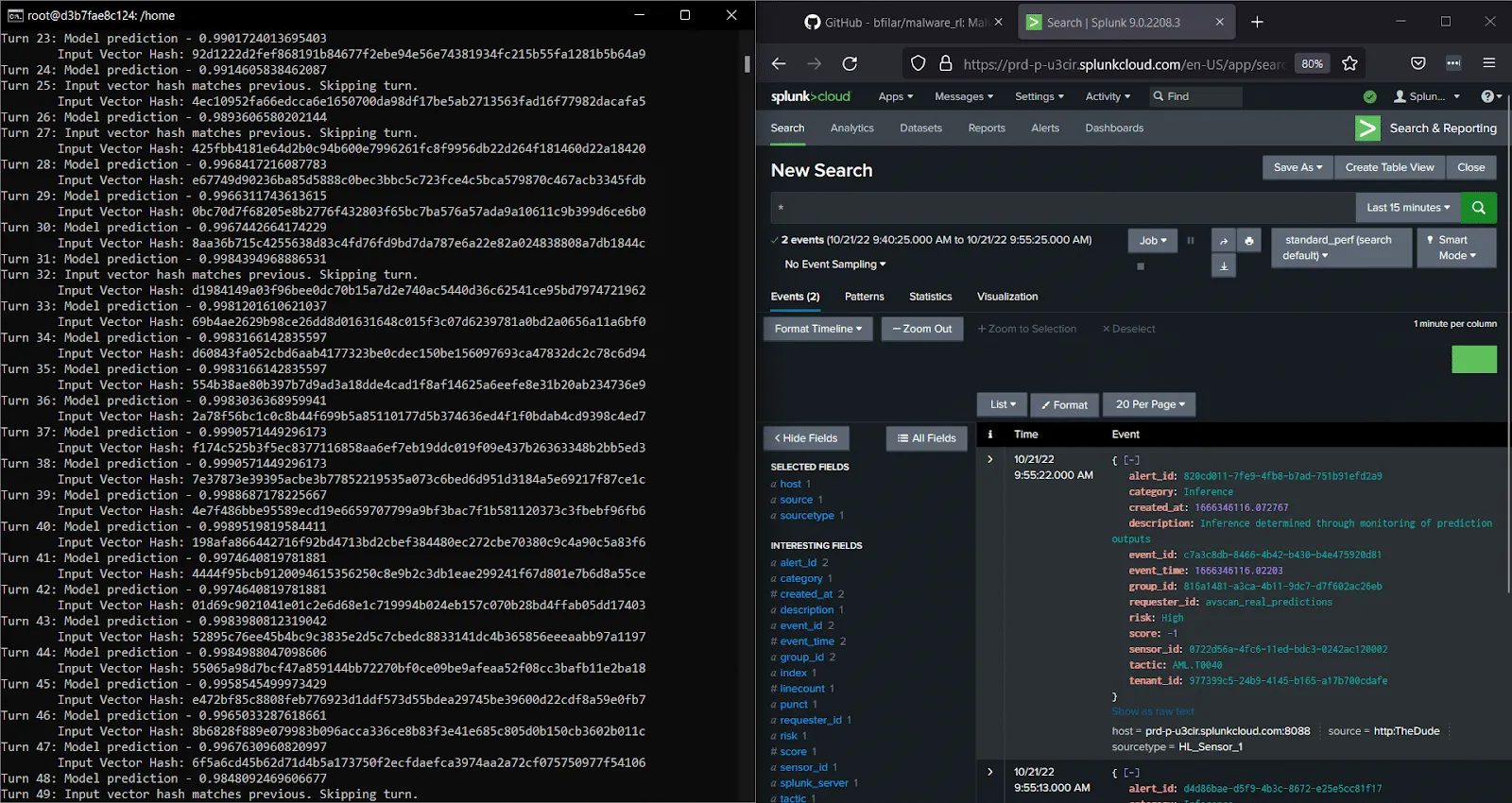

Figure 2: HiddenLayer MLDR architecture

If you’re concerned about exposing your sensitive data to us, don’t worry - we’ve got you covered. Our MLDR solution is post-vectorization, meaning we don’t see any of your sensitive data, nor can we reconstruct it. In simple terms, ML models convert all types of input data - be it an image, audio, text, or tabular data - into numerical ‘vectors’ before it can be ingested. We step in after this process, meaning we can only see a series of floating-point numbers and don’t have access to the input in its original form at any point. In this way, we respect the privacy of your data and - by extension - the privacy of your users.

The Client

When a request is sent to the model, the HiddenLayer client forwards anonymized feature vectors to the HiddenLayer API, where our detection magic takes place. The cloud-based approach helps us to be both lightweight on the device and keep our detection methods obfuscated from adversaries who might try to subvert our defenses.

The client can be installed using a single command and seamlessly integrated into your MLOps pipeline in just a few minutes. When we say seamless, we mean it: in as little as three lines of code, you can start sending vectors to our API and benefitting from the platform.

To make deployment easy, we offer language-specific SDKs, integrations into existing MLOps platforms, and integrations into ML cloud solutions.

Detecting an Attack

While our detections are proprietary, we can reveal that we use a combination of advanced heuristics and machine-learning techniques to identify anomalous actions, malicious activity, and troubling behavior. Some adversaries are already leveraging ML algorithms to attack machine learning, but they’re not the only ones who can fight fire with fire!

Alerting

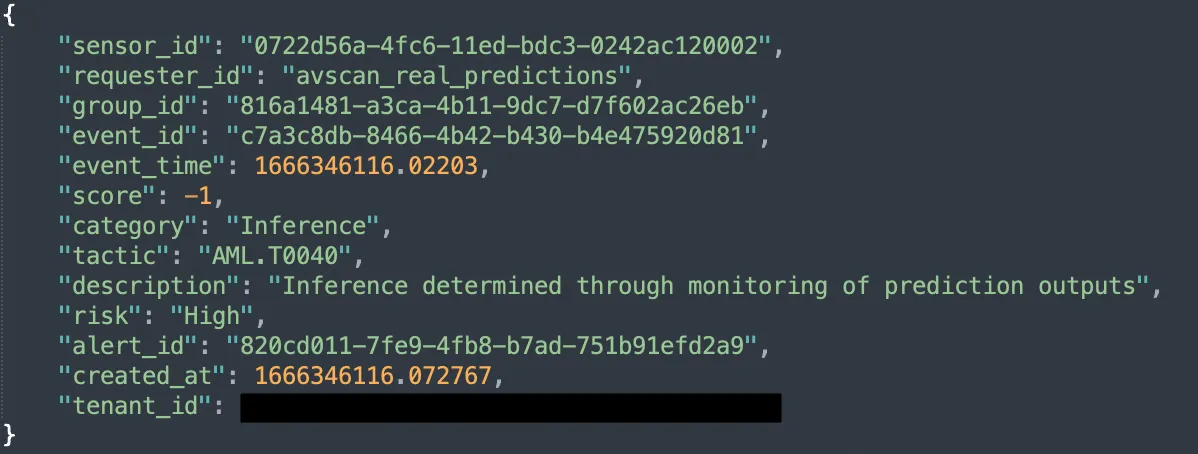

To be useful, a detection requires its trusty companion - the alert. MLDR offers multiple ways to consume alerts, be it from our REST API, the HiddenLayer dashboard, or SIEM integration for existing workflows. We provide a number of contextual data points which enable you to understand the when, where, and what happened during an attack on your models. Below is an example of the JSON-formatted information provided in an alert on an ongoing inference attack:

Figure 3: An example of a JSON-formatted alert from HiddenLayer MLDR

We align with MITRE ATLAS (Adversarial Threat Landscape for Artificial-Intelligence Systems), ensuring we have a working standard for adversarial machine learning attacks industry-wide. Complementary to the well-established MITRE ATT&CK framework, which provides guidelines for classifying traditional cyberattacks, ATLAS was introduced in 2021 and covers tactics, techniques, and case studies of attacks against machine learning systems. An alert from HiddenLayer MLDR specifies the category, description, and ATLAS tactic ID to help correlate known attack techniques with the ATLAS database.

SIEM Integration

Security Information and Event Management technology (SIEM) is undoubtedly an essential part of a workflow for any modern security team - which is why we chose to integrate with Splunk and DataDog from the get-go. Our intent is to bring humans into the loop, allowing the SOC analysts to triage alerts, which they can then escalate to the data science team for detailed investigation and remediation.

Figure 4: An example of an MLDR alert in Splunk

Responding to an Attack

If you fall victim to an attack on your machine learning system and your model gets compromised, retraining the model might be the only viable course of action. There are no two ways about it - model retraining is expensive, both in terms of time and effort, as well as money/resources - especially if you are not aware of an attack for weeks or months! With the rise of automated adversarial ML frameworks, attacks against ML are set to become much more popular - if not mainstream - in the very near future. Retraining the model after each incident is not a sustainable solution if the attacks occur on a regular basis - not to mention that it doesn’t solve the problem at all.

Fortunately, if you are able to detect an attack early enough, you can also possibly stop it before it does significant damage. By restricting user access to the model, redirecting their traffic entirely, or feeding them with fake data, you can thwart the attacker’s attempts to poison your dataset, create adversarial examples, extract sensitive information, or steal your model altogether.

At HiddenLayer, we’re keeping ourselves busy working on novel methods of defense that will allow you to counter attacks on your ML system and give you other ways to respond than just model retraining. With HiddenLayer MLDR, you will be able to:

- Rate limit or block access to a particular model or requestor.

- Alter the score classification to prevent gradient/decision boundary discovery.

- Redirect traffic to profile ongoing attacks.

- Bring a human into the loop to allow for manual triage and response.

Attack Scenarios

To showcase the vulnerability of machine learning systems and the ease with which they can be attacked, we tested a few different attack scenarios. We chose four well-known adversarial ML techniques and used readily available open-source tooling to perform these attacks. We were able to create adversarial examples that bypass malware detection and fraud checks, fool an image classifier, and create a model replica. In each case, we considered possible detection techniques for our MLDR.

MalwareRL - Attacking Malware Classifier Models

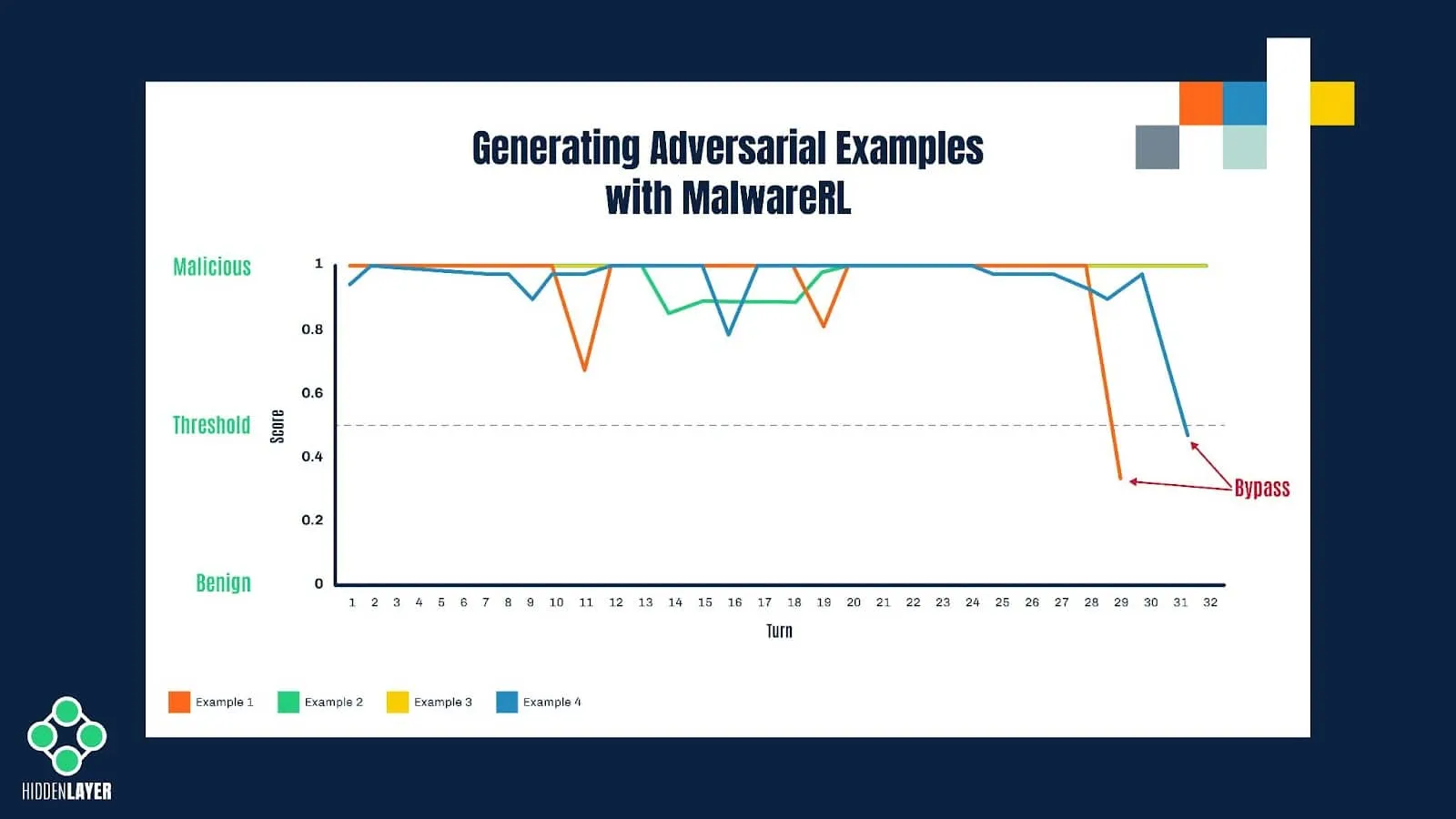

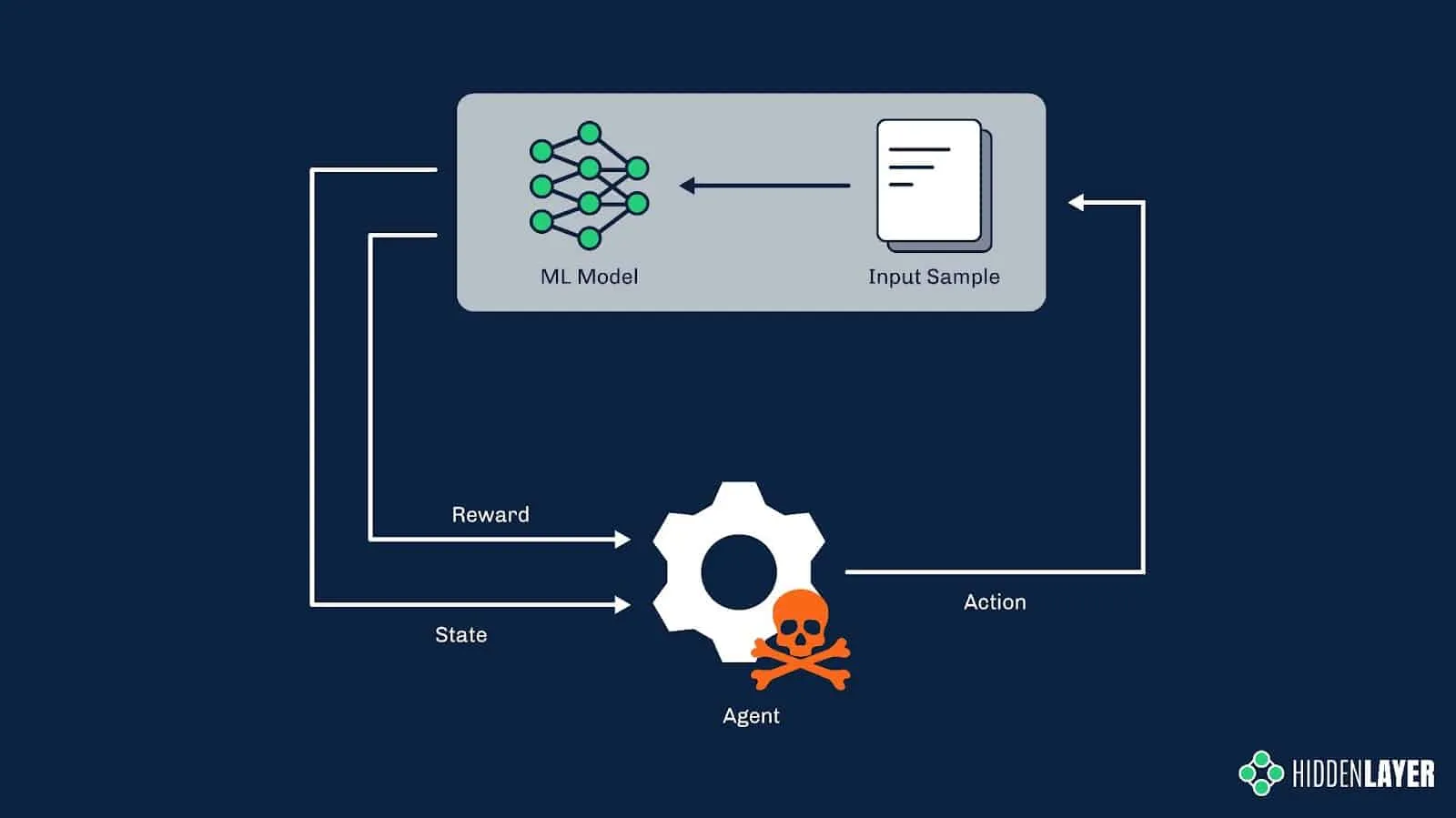

Considering our team’s history in the anti-virus industry, attacks on malware classifiers are of special significance to us. This is why frameworks such as MalwareGym and its successor MalwareRL immediately caught our attention. MalwareRL uses an inference-based attack, coupled with a technique called reinforcement learning, to perturb malicious samples with ‘good’ features, i.e., features that would make the sample look like a piece of clean software to the machine learning model used in an anti-malware solution.

The framework takes a malicious executable and slightly modifies it without altering its functionality (e.g., by adding certain strings or sections, changing specific values in the PE header, etc.) before submitting it to the model for scoring. The new score is recorded, and if it still falls into the “malicious” category, the process is repeated with different combinations of features until the scoring changes enough to flip the classification to benign. The resulting sample remains a fully working executable with the same functionality as the original one; however, it now evades detection.

Figure 5: Illustration of the process of creating adversarial examples with MalwareRL

Although it could be achieved by crude brute-forcing with randomly selected features, the reinforcement learning technique used in MalwareRL helps to significantly speed up and optimize this process of creating “adversarial examples”. It does so by rewarding desired outcomes (i.e., perturbations that bring the score closer to the decision boundary) and punishing undesired ones. Once the score is returned by the model, the features used to perturb the sample are given specific weights, depending on how they affect the score. Combinations of the most successful features are then used in subsequent turns.

Figure 6: Reinforcement learning in adversarial settings

MalwareRL is implemented as a Docker container and can be downloaded, deployed, and used in an attack in a matter of minutes.

MalwareRL was naturally one of the first things we tossed at our MLDR solution. First, we’ve implemented the MLDR client around the target model to intercept input vectors and output scores for every single request that comes through to the model; next, we’ve downloaded the attack framework from GitHub and run it in a docker container. Result - a flurry of alerts from the MLDR sensor about a possible inference-based attack!

Figure 7: MLDR in action - detecting MalwareRL attack

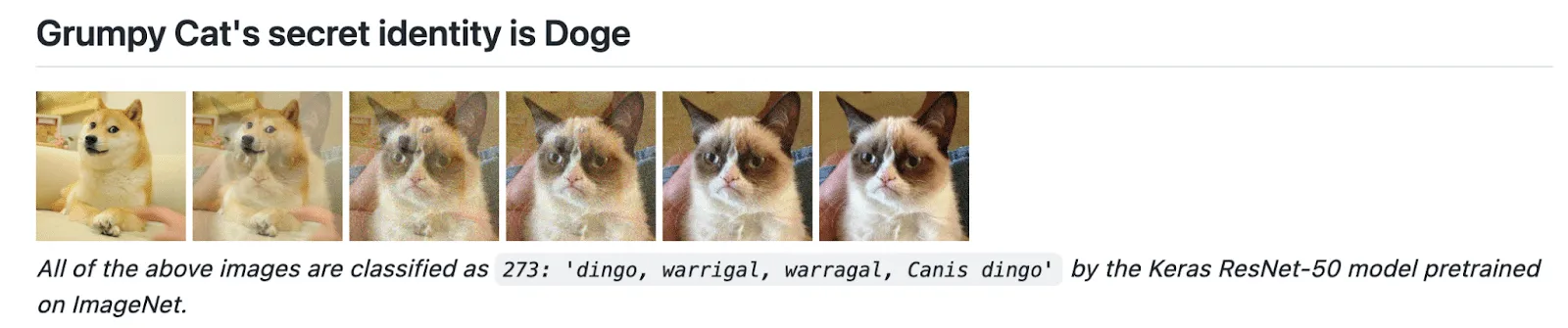

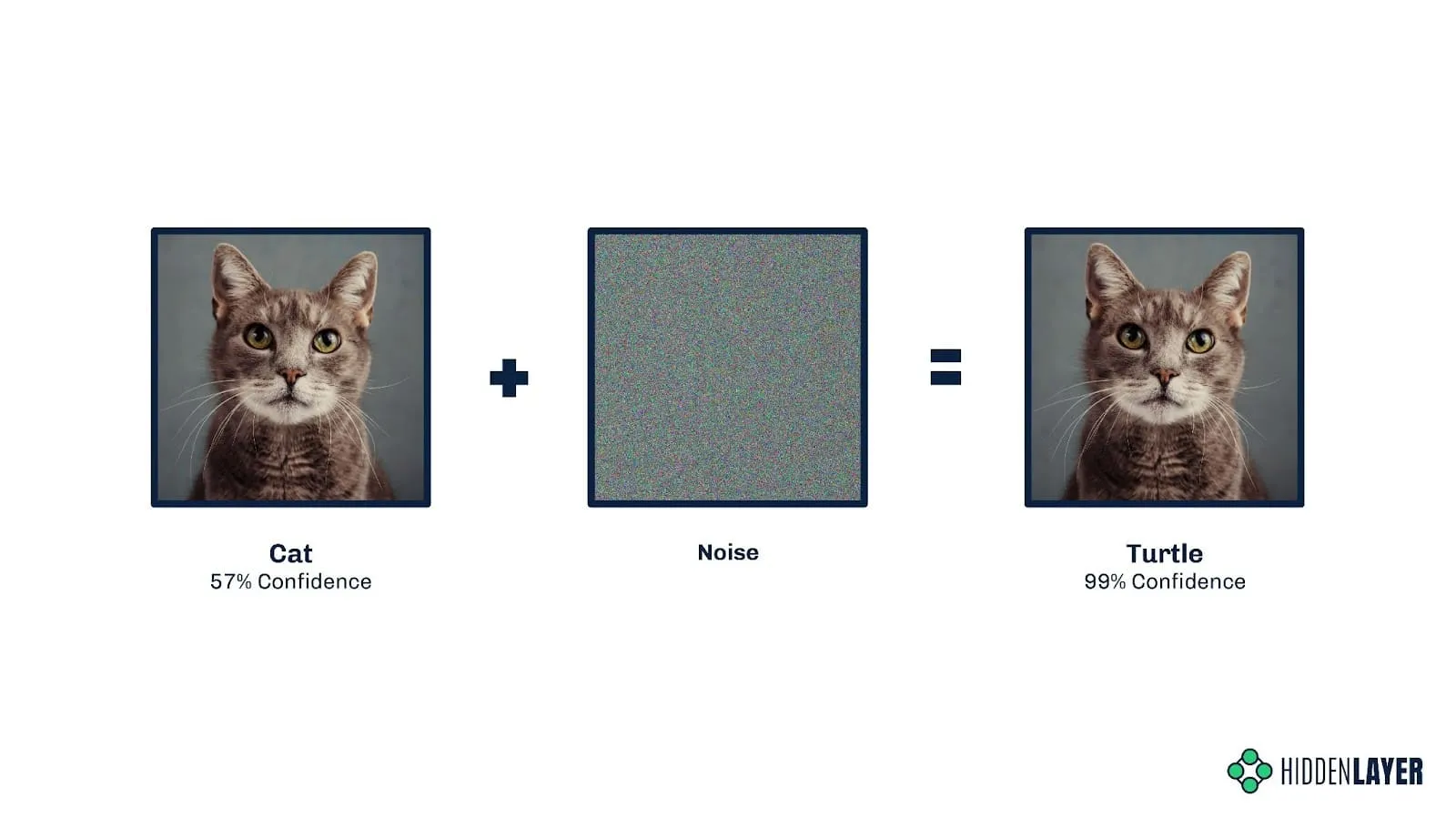

One Pixel Attack - Fooling an Image Classifier

Away from the anti-malware industry, we will now look at how an inference-based attack can be used to bypass image classifiers. One Pixel Attack is one the most famous methods of perturbing a picture in order to fool an image recognition system. As the name suggests, it uses the smallest possible perturbation - a modification to one single pixel - to flip the image classification either to any incorrect label (untargeted attack) or to a specific, desired label (targeted attack).

Figure 8: An example of One Pixel Attack on a gender recognition model

To optimize the generation of adversarial examples, One Pixel Attack implementations use an evolutionary algorithm called Differential Evolution. First, an initial set of adversarial images is generated by modifying the color of one random pixel per example. Next, these pixels’ positions and colors are combined together to generate more examples. These images are then submitted to the model for scoring. Pixels that lower the confidence score are marked as best-known solutions and used in the next round of perturbations. The last iteration returns an image that achieved the lowest confidence score. A successful attack would result in such a reduction in confidence score that will flip the classification of the image.

Figure 9: Differential evolution; source: Wikipedia

We’ve run the One Pixel Attack over a ResNet model trained on the CelebA database. The model was built to recognize a photo of a human face as either male or female. We were able to create adversarial examples with an (often imperceptible!) one-pixel modification that tricked the model into predicting the opposing gender label. This kind of attack can be detected by monitoring the input vectors for large batches of images with very slight modifications.

Figure 10: One-pixel attack demonstration

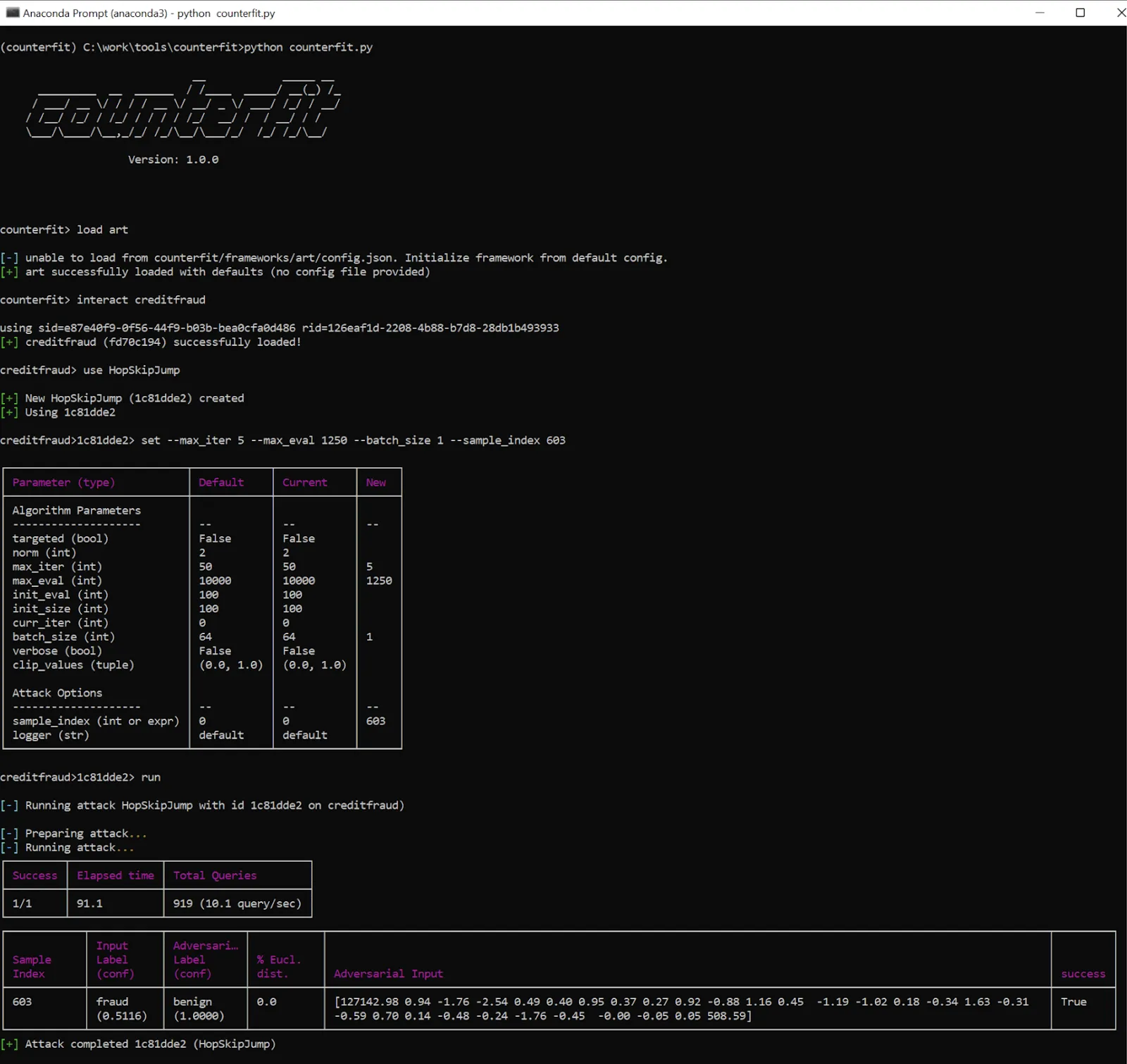

Boundary Attack and HopSkipJump

While One Pixel Attack is based on perturbing the target image in order to trigger misclassification, other algorithms, such as Boundary Attack and its improved version, the HopSkipJump attack, use a different approach.

In Boundary Attack, we start with two samples: the sample we want the model to misclassify (the target sample) and any sample that triggers our desired classification (the adversarial example). The goal is to perturb the adversarial example in such a way that it bears the most resemblance to the target sample without triggering the model to change the predicted class. The Boundary Attack algorithm moves along the model’s decision boundary (i.e., the threshold between the correct and incorrect prediction) on the side of the adversarial class, starting from the adversarial example toward the target sample. At the end of this procedure, we should be presented with a sample that looks indistinguishable from the target image yet still triggers the adversarial classification.

Figure 11: Example of boundary attack, source: GitHub / greentfrapp

The original version of Boundary Attack uses a rejection sampling algorithm for choosing the next perturbation. This method requires a large number of model queries, which might be considered impractical in some attack scenarios. The HopSkipJump technique introduces an optimized way to estimate the subsequent steps along the decision boundary: it uses binary search to find the boundary, estimates the gradient direction, and calculates the step size via geometric progression.

The HopSkipJump attack can be used in many attack scenarios and not necessarily against image classifiers. Microsoft’s Counterfit framework implements a CreditFraud attack that uses the HopSkipJump technique, and we’ve chosen this implementation to test MLDR’s detection capability. In these kinds of inference attacks, often only very minor perturbations are made to the model input in order to infer decision boundaries. This can be detected using various distance metrics over a time series of model inputs from individual requestors.

Figure 12: Launching an attack on a credit card fraud detection model using Counterfit

Adversarial Robustness Toolbox - Model Theft using KnockOffNets

Besides fooling various classifiers and regression models into making incorrect predictions, inference-based attacks can also be used to create a model replica - or, in other words, to steal the ML model. The attacker does not need to breach the company’s network and exfiltrate the model binary. As long as they have access to the model API and can query the input vectors and output scores, the attacker can spam the model with a large amount of specially crafted queries and use the queried input-prediction pairs to train a so-called shadow model. A skillful adversary can create a model replica that will behave almost exactly the same as the target model. All ML solutions that are exposed to the public, be it via GUI or API, are at high risk of being vulnerable to this type of attack.

Knockoff Nets is an open-source tool that shows how easy it is to replicate the functionality of neural networks with no prior knowledge about the training dataset or the model itself. As with MalwareRL, it uses reinforcement learning to improve the efficiency and performance of the attack. The authors claim that they can create a faithful model replica for as little as $30 - it might sound very appealing to some who would rather not spend considerable amounts of time and money on training their own models!

An attempt to create a model replica using KnockOffNets implementation from IBM’s Adversarial Robustness Toolbox can be detected by means of time-series analysis. A sequence of input vectors sent to the model in a specified period of time is analyzed along with predictions and compared to other such sequences in order to detect abnormalities. If all of a sudden the traffic to the model differs significantly from the usual traffic (be it per customer or globally), chances are that the model is under attack.

What’s next?

AI is a vast and rapidly growing industry. Most verticals are already using it to some capacity, with more still looking to implement it in the near future. Our lives are increasingly dependent on decisions made by machine learning algorithms. It’s therefore paramount to protect this critical technology from any malicious interference. The time to act is now, as the adversaries are already one step ahead.

By introducing the first-ever security solution for machine learning systems, we aim to highlight how vulnerable these systems are and underline the urgent need to fundamentally rethink the current approach to AI security. There is a lot to be done and the time is short; we have to work together as an industry to build up our defenses and stay on top of the bad guys.

The few types of attacks we described in this blog are just the tip of the iceberg. Fortunately, like other detection and response solutions, our MLDR is extensible, allowing us to continuously develop novel detection methods and deploy them as we go. We recently announced our MLSec platform, which comprises MLDR, Model Scanner, and Security Audit Reporting. We are not stopping there. Stay tuned for more information in the coming months.

The Tactics Techniques of Adversarial Machine Learning

Previously, we discussed the emerging field of adversarial machine learning, illustrated the lifecycle of an ML attack from both an attacker’s and defender’s perspective, and gave a high-level introduction to how ML attacks work. In this blog, we take you further down the rabbit hole by outlining the types of adversarial attacks that should be on your security radar.

Attacks on Machine Learning – Explained

Introduction

Previously, we discussed the emerging field of adversarial machine learning, illustrated the lifecycle of an ML attack from both an attacker’s and defender’s perspective, and gave a high-level introduction to how ML attacks work. In this blog, we take you further down the rabbit hole by outlining the types of adversarial attacks that should be on your security radar.

We aim to acquaint the casual reader with adversarial ML vocabulary and explore the various methods by which an adversary can compromise models and conduct attacks against ML/AI systems. We introduce attacks performed in both controlled and real-world scenarios as well as highlight open-source software for offensive and defensive purposes. Finally, we touch on what we’ll be working towards in the coming months to help educate ML practitioners and cybersecurity experts in protecting their most precious assets from bad actors, who seek to degrade the business value of AI/ML.

Before we begin, it is worth noting that while “adversarial machine learning” typically refers to the study of mathematical attacks (and defenses) on the underlying ML algorithms, people often use the term more freely to encompass attacks and countermeasures at any point during the MLOps lifecycle. MLSecOps is also an excellent term when discussing the broader security ecosystem during the operationalization of ML and can help to prevent confusion with pure AML.

Attack breakdown

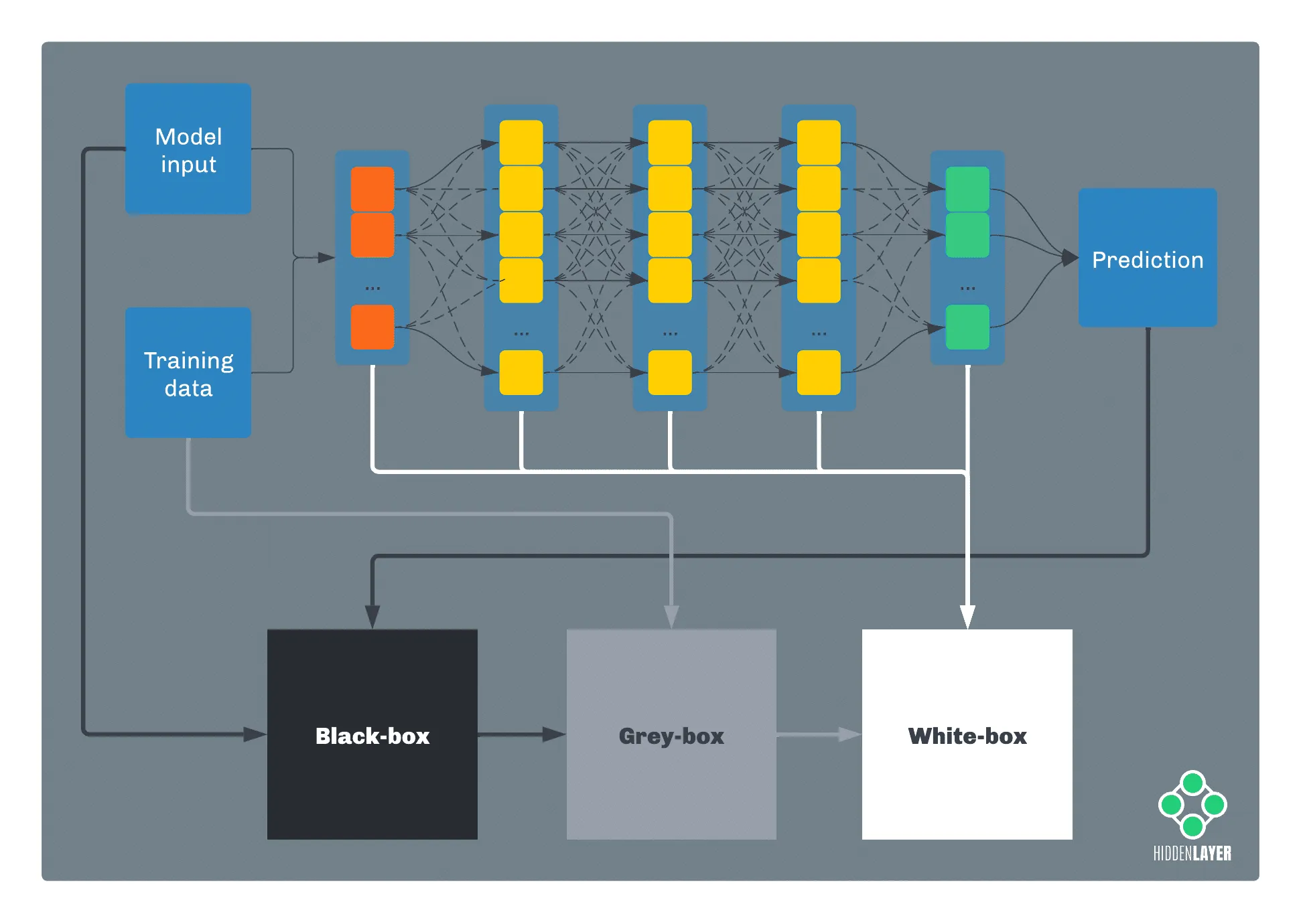

Traditionally, attacks against machine learning have been broadly categorized alongside two axes: the information the attacker possesses and the timing of the attack.

In terms of information, if an attacker has full knowledge of a model, such as parameters, features, and training data, we’re talking about a white-box attack. Conversely, if the attacker has no knowledge whatsoever about the inner workings of the model and just has access to its predictions, we call it a black-box attack. Anything in between these two falls into the grey-box category.

In practice, an adversary will often start from a black-box perspective and attempt to elevate their knowledge, for example, by performing inference or oracle attacks (more on that later). Often, sensitive information about a target model can be acquired by more traditional means, such as open-source intelligence (OSINT), social engineering, cyberespionage, etc. Occasionally, marketing departments will even reveal helpful details on Twitter:

In terms of timing, an attacker can either target the learning algorithm during the model training phase or target a pre-trained model when it makes a decision.

Attacks during training time aim to influence the learning algorithm by tampering with the training data, leading to an inaccurate or biased model (known as data poisoning attacks).

Decision-time attacks can be divided into two major groups: oracle attacks, where the attacker queries the model to obtain clues about the model’s internals or the training data; and evasion attacks, in which the attacker tries to find the way to fool the model to evade the correct prediction.

Both training-time and decision-time attacks often leverage statistical risk vectors, such as bias and drift. If an attack relies on exploiting existing anomalies in the model, we call it a statistical attack.

While all the attacks can be assigned a label associated with the information axis (an attacker either has knowledge about the model or has not), the same is not always true for the timing axis. Model hijacking attacks, which rely on embedding malicious payloads in an ML model through tampering and data deserialization flaws, can either occur at training or at decision time. For instance, an attacker could insert a payload by tampering with the model at training time or by altering a pre-trained model offered for distribution via a model zoo, such as HuggingFace.

Now that we understand the basic anatomy of attack tactics let’s delve deeper into some techniques.

Training-Time Attacks

The model training phase is one of the crucial phases of building an ML solution. During this time, the model learns how to behave based on the inputs from the training dataset. Any malicious interference in the learning process can significantly impact the reliability of the resulting model. As the training dataset is the usual target for manipulation at training time, we use the term data poisoning for such attacks.

Data Poisoning Attacks

Suppose an adversary has access to the model’s training dataset or possesses the ability to influence it. In this case, they can manipulate the data so that the resulting model will produce biased or simply inaccurate predictions. In some cases, the attacker will only be interested in lowering the overall reliability of the model by maximizing the ratio of erroneous predictions, for example, to discredit the model’s efficiency or to get the opposite outcome in a binary classification system. In more targeted attacks, the adversary’s aim is to selectively bias the model, so it gives wrong predictions for specific inputs while being accurate for all others. Such attacks can go unnoticed for an extended period of time.

Attackers can perform data poisoning in two ways: by modifying entries in the existing dataset (for example, changing features or flipping labels) or injecting the dataset with a new, specially doctored portion of data. The latter is hugely relevant as many online ML-based services are continually re-trained on user-provided input.

Let’s take the example of online recommendation mechanisms, which have become an integral part of the modern Internet, having been widely implemented across social networks, news portals, online marketplaces, and media streaming platforms. The ML models that assess which content will be most interesting/relevant to specific users are designed to change and evolve based on how the users interact with the system. An adversary can manipulate such systems by supplying large volumes of “polluted” content, i.e., content that is meant to sway the recommendations one way or the other. Content, in this context, can mean anything that becomes features for the model based on a user’s behavior, including site visits, link clicks, posts, mentions, likes, etc.

Other systems that make use of online-training models or continuous-learning models and are therefore susceptible to data poisoning attacks include:

- Text auto-complete tools

- Chatbots

- Spam filters

- Intrusion detection systems

- Financial fraud prevention

- Medical diagnostic tools

Data poisoning attacks are relatively easy to perform even for uninitiated adversaries because creating “polluted” data can often be done intuitively without needing any specialist knowledge. Such attacks happen daily: from manipulating text completion mechanisms to influencing product reviews to political disinformation campaigns. F-Secure published a rather pertinent blog on the topic outlining ‘How AI is already being poisoned against you.’

Byzantine attacks

In a traditional machine learning scenario, the training data resides within a single machine or data center. However, many modern ML solutions opt for a distributed learning method called federated (or collaborative) learning, where the training dataset is scattered amongst several independent devices (think Siri, being trained to recognize your voice). During federated learning, the ML model is downloaded and trained locally on each participating edge device. The resulting updates are either pushed to the central server or shared directly between the nodes. The local training dataset is private to the participating device and is never shared outside of it.

Federated learning helps companies maximize the amount and diversity of the training data while preserving the data privacy of collaborating users. Offering such advantages, it’s not surprising that this approach has become widely used in various solutions: from everyday-use mobile phone applications to self-driving cars, manufacturing, and healthcare. However, delegating the model training process to an often random and unverified cohort of users amplifies the risk of training-time attacks and model hijacking.

Attacks on federated learning in which malicious actors operate one or more participating edge devices are called byzantine attacks. The term comes from distributed computing systems, where a fault of one of the components might be difficult to spot and correct due to the very component malfunction (Byzantine fault). Likewise, it might be challenging in a federated learning network to spot malicious devices that regularly tamper with the training process or even hijack the model by injecting it with a backdoor.

Decision-Time Attacks

Decision-time attacks (a.k.a. testing-time attacks, a.k.a inference-time attacks) are attacks performed against ML/AI after it has been deployed in some production setting, whether on the endpoint or in the cloud. Here the ML attack surface broadens significantly as adversaries try to discover information about training data and feature sets, evade/bypass classifications, and even steal models entirely!

Terminology

Several decision-time attacks rely on inference to create adversarial examples, so let’s first give a quick overview of what they are and how they’re crafted before we explore some more specific techniques.

Adversarial Examples

Maliciously crafted inputs to a model are referred to as adversarial examples, whether the features are extracted from images, text, executable files, audio waveforms, etc., or automatically generated. The purpose of an adversarial example is typically to evade classification (for example, dog to cat, spam to not spam, etc.), but they can also be helpful for an attacker to learn the decision boundaries of a model.

In a white-box scenario, several algorithms exist to auto-generate adversarial examples, for example, Gradient-based evasion attack, Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD). In a black-box scenario, nothing beats a bit of old-fashioned domain expertise, where understanding the feature space, combined with an attacker’s intuition, can help to narrow down the most impactful features to selectively target for modification.

Further approaches exist to help generate and rank vast quantities of adversarial examples en-masse, with reinforcement learning and generative adversarial networks (GANs) proving a popular choice amongst attackers for bulk generating adversarial examples to conduct evasion attacks and perform model theft.

Inference

At the core of most, if not all, decision-time attacks lie inference, but what is it?

In the broader context of machine learning, inference is the process of running live data (as opposed to the training/test/validation set) on the already-trained model to obtain the model scores and decision boundaries. In other words, inference is the post-deployment phase, where the model infers the predictions based on the features of input data. Decision-time and inference-time terms are often used interchangeably.

In the context of adversarial ML, we talk about inference when a specific data mining technique is used to leak sensitive information about the model or training dataset. In this technique, the knowledge is inferred from the outputs the model produces for a specially prepared data set.

In the following example, the unscrupulous attacker submits the accepted input data, e.g., a vectorized image, binary executable, etc., and records the results, i.e., the model’s classification. This process is repeated cyclically, with the attacker continually modifying the input features to derive new insight and infer the decisions the model makes.

Typically, the greater an adversaries’ knowledge of your model, features, and training data, the easier it becomes to generate subtly modified adversarial examples that cross decision boundaries, resulting in misclassification by the model and revealing decision boundaries to the attacker, which can help craft subsequent attacks.

Evasion Attacks

Evasion attacks, known in some circles as model bypasses, aim to perturb input to a model to produce misclassifications. In simple terms, this could be modifying pixels in an image by adding noise or rotating images, resulting in a model misclassifying an image of a cat as a fox, for example, which would be an unmitigated disaster for biometric cat flap access control systems! Attackers have been tampering with model input features since the advent of Bayesian email spam filtering, adding “good” words to emails to decrease the chances of ML classifiers tagging a mail as spam.

Creating such adversarial examples usually requires decision-time access to the model or a surrogate/proxy model (more on this in a moment). With a well-trained surrogate model, an attacker can infer if the adversarial example produces the desired outcome. Unless an attacker is extremely fortunate to create such an example without any testing, evasion attacks will almost always use inference as a starting point.

A notable instance of an evasion attack was the Skylight Cyber bypass of the Cylance anti-virus solution in 2019, which leveraged inference to determine a subset of strings that, when embedded in malware, would trick the ML model into classifying malicious software as benign. This attack spawned several anti-virus bypass toolkits such as MalwareGym and MalwareRL, where evasion attacks have been combined with reinforcement learning to automatically generate mutations in malware that make it appear benign to malware classification models.

Oracle Attacks

Not to be mistaken with Oracle, the corporate behemoth; oracle attacks allow the attacker to infer details about the model architecture, its parameters, and the data the model was trained on. Such attacks again rely fundamentally on inference to gain a grey-box understanding of the components of a target model and potential points of vulnerability therein. The NIST Taxonomy and Terminology of Adversarial Machine Learning breaks down oracle attacks into three main subcategories:

Extraction Attacks - “an adversary extracts the parameters or structure of the model from observations of the model’s predictions, typically including probabilities returned for each class.”

Inversion Attacks - “the inferred characteristics may allow the adversary to reconstruct data used to train the model, including personal information that violates the privacy of an individual.”

Membership Inference Attacks - “the adversary uses returns from queries of the target model to determine whether specific data points belong to the same distribution as the training dataset by exploiting differences in the model’s confidence on points that were or were not seen during training.”

Hopefully, by now, we’ve adequately explained adversarial examples, inference, evasion attacks, and oracle attacks in a way that makes sense. The lines between these definitions can appear blurred depending on what taxonomy you subscribe to, but the important part is the context of how they work.

Model Theft

So far, we’ve focused on scenarios in which the adversaries aim to influence or mislead the AI, but that’s not always the case. Intellectual property theft - i.e., stealing the model itself - is a different but very credible motivation for an attack.

Companies invest a lot of time and money to develop and train advanced ML solutions that outperform their competitors. Even if the information about the model and the dataset it’s trained on is not publicly available, the users can often query the model (e.g., through a GUI or an API), which might be enough for the adversary to perform an oracle attack.

The information inferred via oracle attacks can not only be used to improve further attacks but can also help reconstruct the model. One of the most common black-box techniques involves creating a so-called surrogate model (a.k.a. proxy model, a.k.a shadow model) designed to approximate the decision boundaries of the attacked model. If the approximation is accurate enough, we can talk of de-facto model replication.

Such replicas may be used to create adversarial examples in evasion attacks, but that’s not where the possibilities end. A dirty-playing competitor could attempt model theft to give themselves a cheap and easy advantage from the beginning, without the hassle of finding the right dataset, labeling feature vectors, and bearing the cost of training the model themselves. Stolen models could even be traded on underground forums in the same manner as confidential source code and other intellectual property.

Model theft examples include the proof-of-concept code targeting the ProofPoint email scoring model (GitHub - moohax/Proof-Pudding: Copy cat model for Proofpoint) as well as intellectual property theft through model replication of Google Translate (Imitation Attacks and Defenses for Black-box Machine Translation Systems).

Statistical Attack Vectors

In discussing the various attacks to feature in this blog, we realized that bias and drift might also be considered attack vectors, albeit in the nontraditional sense. That is not to say that we wish to redefine these intrinsic statistical features of ML, more so to introduce them as potential vectors for attack when an attacker’s wish is to incur ill outcomes such as reputation loss upon the target company or manipulate a model into inaccurate classification. The next question is, do we consider them training time attacks or decision time attacks? The answer lies somewhere in the middle. In models trained in a ‘set and forget’ fashion, bias and drift are often considered only at initial training or retraining time. However, in instances where models are continually trained on incoming data, such as the case of recommendation algorithms, bias and drift are very much live factors that can be influenced using inference and a little elbow grease. Given the variability of when these features can be introduced and exploited, we elected to use the term statistical attack to represent this nuanced attack vector.

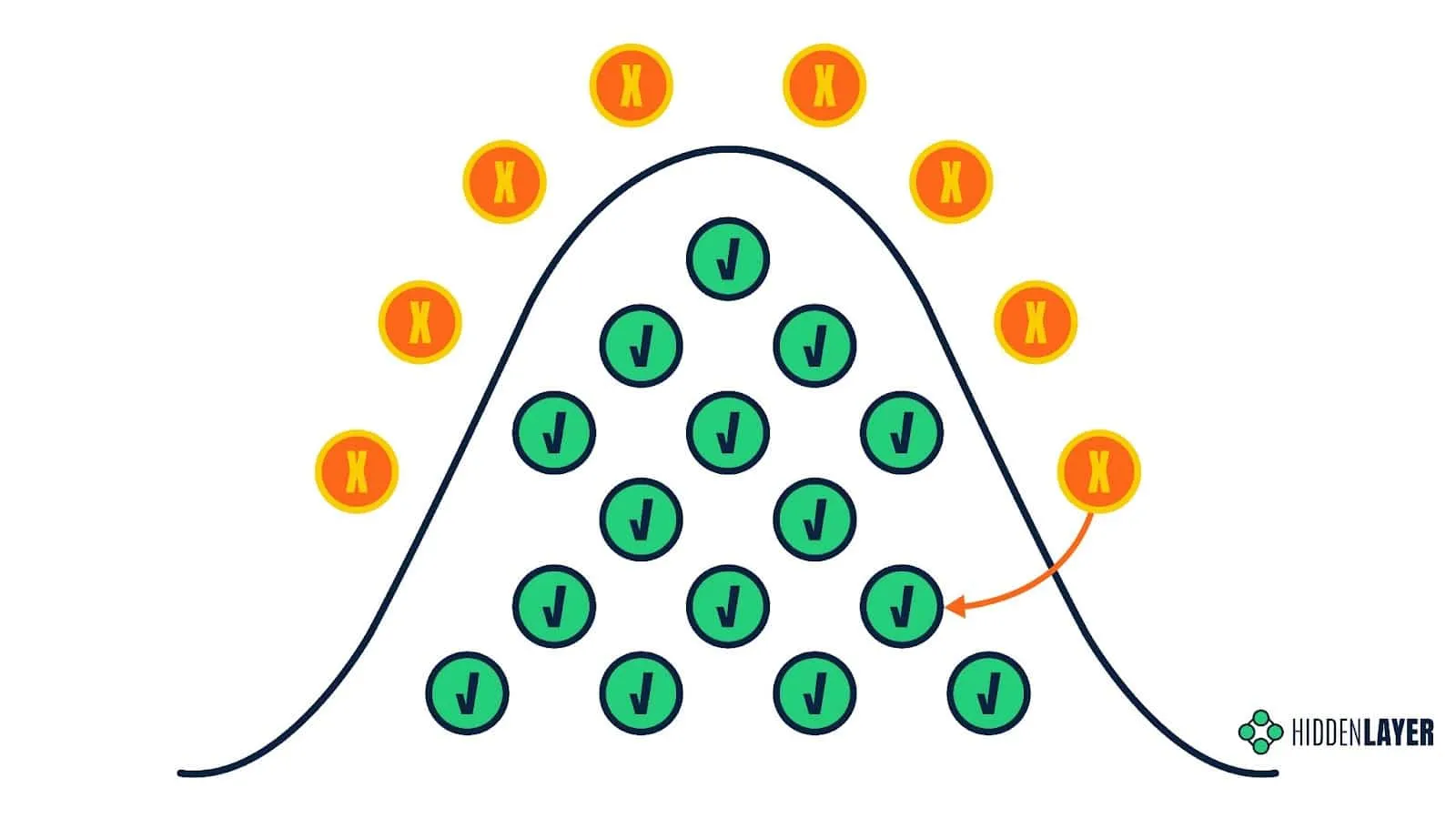

Bias

In the context of ML, bias can be viewed through a couple of different lenses. In the statistical sense, bias is the difference between the derived results (i.e., model prediction) and what is known to be fact or ground truth. From a more general perspective, bias can be considered a prejudice or skewing towards a particular data point. Models that contain this systemic error are said to be either high-bias or low-bias, with a model that lies in between being considered a ‘good fit’ (i.e., little difference between the prediction and ground truth). High/Low bias is commonly referred to as underfitting or overfitting, respectively. It is commonly said that an ML model is only good as its training data, and in this case, biased training data will produce biased results. See below, where a face depixelizer model transforms a pixelized Barrack Obama into a caucasian male:

Image Source: https://twitter.com/Chicken3gg/status/1274314622447820801

While bias may sound like an issue for data scientists and ML engineers to consider, the potential ramifications of a model which expresses bias extend far beyond. As we touched on in our blog: Adversarial Machine Learning - The New Frontier, ML makes critical decisions that directly impact daily life. For example, a mortgage loan ML model with high bias may refuse applications of minority groups at a higher rate. If this sounds oddly familiar, you may have seen this article from MIT Technology Review last year, which discusses exactly that.

You may be wondering by now how bias could be introduced as a potential attack vector, and the answer to that largely depends on how ambitious or determined your attacker is. Attackers may look to discover forms of bias that may already exist in a model or go as far as to introduce bias by poisoning the training data. The intended consequence or outcome of such an attack being to cause socio-economic damage or reputational harm to the company or organization in question.

Drift

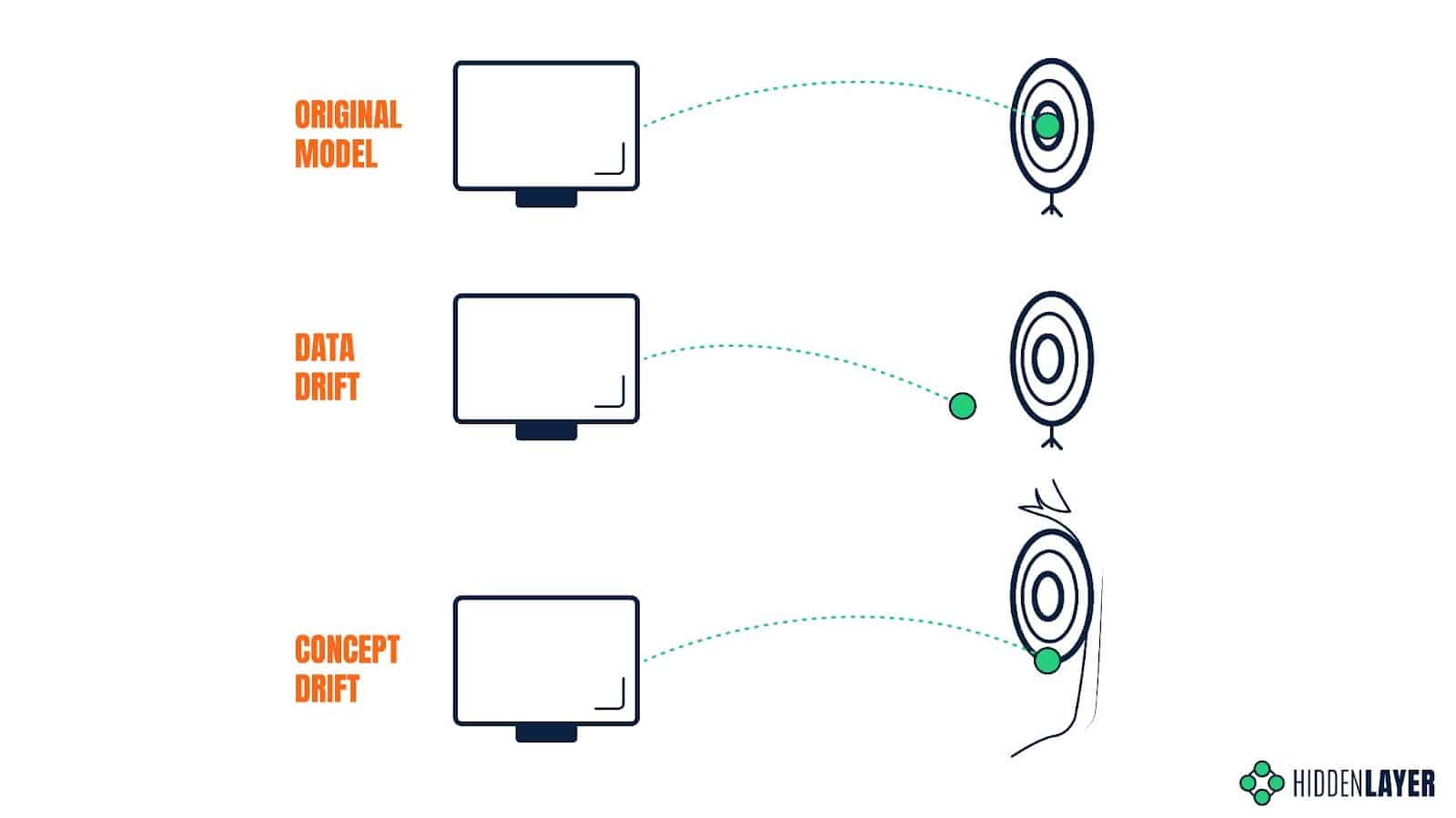

The accuracy of an ML model can spontaneously degrade over time due to unforeseen or unconsidered changes in the environment or input. A model trained on historical data will perform poorly if the distribution of variables in production data significantly differs from the training dataset. Even if the model is periodically retrained to keep on top of gradually changing trends and behaviors, an unexpected event can have a sudden impact on the input data and, therefore, on the quality of the predictions. The susceptibility of model predictions to changes in the input data is called data drift.

The model’s predictive power can also be affected if the relationship between the input data and the expected output changes, even if the distribution of variables stays the same. The predictions that would be considered accurate at some point in time might prove completely inaccurate under new circumstances. Take a search engine and the Covid pandemic as an example: since the outbreak, people searching for keywords such as “coronavirus” are far more likely to look for results related to Covid-19 and not just generic information about coronaviruses. The expected output for this specific input has changed, so the results that would be valid before the outbreak might now seem less relevant. The susceptibility of model predictions to changes in the expected output is called concept drift.

Attackers can induce data drift using data poisoning techniques, or exploit concept drift to achieve their desired outcomes.

Model Hijacking Attacks

Outside of training/decision-time attacks, we find ourselves also exploring other attacks against models, be it tampering with weights and biases of neural networks stored on-disk or in-memory, or ways in which models can be trained (or retrained) to include “backdoors.” We refer to these attacks as “model hijacking,” which may result in an attacker being able to intercept model features, modify predictions or even deploy malware via pre-trained models.

Backdoored Models

In the context of adversarial machine learning, the term “backdoor” doesn’t refer to a traditional piece of malware that an attacker can use to access a victim’s computer remotely. Instead, it describes a malicious module injected into the ML model that introduces some secret and unwanted behavior. This behavior can then be triggered by specific inputs, as defined by the attacker.

In deep neural networks, such a backdoor is referred to as a neural payload and consists of two elements: the first is a layer (or network of layers) implementing the trigger detection mechanism and the second is some conditional logic to be executed when specific input is detected. As demonstrated in the DeepPayload: Black-box Backdoor Attack on Deep Learning Models through Neural Payload Injection paper, a neural payload can be injected into a compiled model without the need for the attacker to have access to the underlying learning algorithm or the training process.

A skillfully backdoored model can appear very accurate on the surface, performing as expected with the regular dataset. However, it will misclassify every input that is perturbed in a certain way - a way that is only known to the adversary. This knowledge can then be sold to any interested party or used to provide a service that will ensure the customers get the desired outcome.

As opposed to data poisoning attacks, which can influence the model through tampering with the training dataset, planting a backdoor in an ML model requires access to the model - be it in raw or compiled/binary form. We mentioned before that in many scenarios, models are re-trained based on the user’s input, which means that the user has de facto control over a small portion of the training dataset. But how can a malicious actor access the ML model itself? Let’s consider two risk scenarios below.

Hijacking of Publicly Available Models

Many ML-based solutions are designed to run locally and are distributed together with the model. We don’t have to look further than the mobile applications hosted on Google Play or Apple Store. Moreover, specialized repositories, or model zoos, like Hugging Face, offer a range of free pre-trained models; these can be downloaded and used by entry-level developers in their apps. If an attacker finds a way to breach the repository the model/application is hosted on, they could easily replace it with its backdoored version. This form of tampering could be mitigated by introducing a requirement for cryptographic signing and model verification.

Malevolent Third-Party Machine Learning Contractors

Maintaining the competitiveness of an AI solution in a rapidly evolving market often requires solid technical expertise and significant computational resources. Smaller businesses that refrain from using publicly available models might instead be tempted to outsource the task of training their models to a specialized third party. Such an approach can save time and money, but it requires much trust, as a malevolent contractor could easily plant a backdoor in the model they were tasked to train.

The idea of planting backdoors in deep neural networks was recently discussed at length from both white-box and black-box perspectives.

Trojanized Models

Although not an adversarial ML attack in the strictest sense of the term, trojanized models aim to exploit weaknesses in model file formats, such as data deserialization vulnerabilities and container flaws. Attacks arising from trojanized models may include:

- Remote code execution and other deserialization vulnerabilities (neatly highlighted by Fickling - A Python pickling decompiler and static analyzer).

- Denial of service (for example, Zip bombs).

- Staging malware in ML artifacts and container file formats.

- Using steganography to embed malicious code into the weights and biases of neural networks, for example, EvilModel.

With a lack of cryptographic signing and verification of ML artifacts, model trojanizing can be an effective means of performing initial compromise (i.e., deploying malware via pre-trained models). It is also possible to perform more bespoke attacks to subvert the prediction process, as highlighted by pytorchfi, a runtime fault injection tool for PyTorch.

Vulnerabilities

It would be remiss not to mention more traditional ways in which machine learning systems can be affected. Since ML solutions naturally depend on software, hardware, and (in most cases) network connection, they face the same threats as any other IT system. They are exposed to vulnerabilities in 3rd party software and operating system; they can be exploited through CPU and GPU attacks, such as side-channel and memory attacks; finally, they can fall victim to DDoS attacks, as well as traditional spyware and ransomware.

GPU-focused attacks are especially relevant here, as complex deep neural networks (DNNs) usually rely on graphic processors for better performance. Unlike modern CPUs, which evolved to implement many security features, GPUs are often overlooked as an attack vector and, therefore, poorly protected. A method of recovering raw data from the GPU was presented in 2016. Since then, several academic papers have discussed DNN model extraction from GPU memory, for example, by exploiting context-switching side channel or via Hermes attack. Researchers also managed to invalidate model computations directly inside GPU memory in the so-called Mind Control attack against embedded ML solutions.

Discussing broader security issues surrounding IT systems, such as software vulnerabilities, DDoS attacks, and malware, is outside of the scope of this article, but it’s definitely worth underlining that threats to ML solutions are not limited to attacks against ML algorithms and models.

Defending Against Adversarial Attacks

At the risk of doubling the length of this blog, we have decided to make adversarial ML defenses the topic of our subsequent write-up, but it’s worth touching on a couple of high-level considerations now.

Each stage of the MLOps lifecycle has differing security considerations and, consequently, different forms of defense. When considering data poisoning attacks, role-based access controls (RBAC), evaluating your data sources, performing integrity checks, and hashing come to the fore. Additionally, tools such as IBM’s Adversarial Robustness Toolbox (ART) and Microsoft’s Counterfit can help to evaluate the “robustness” of ML/AI models. With the dissemination of pre-trained models, we look to model signing and trusted source verification. In terms of defending against decision time attacks, techniques such as gradient masking and model distillation can also increase model robustness. In addition, a machine learning detection and response (MLDR) solution can not only alert you if you’re under attack but provide mitigation mechanisms to thwart adversaries and offer contextual threat intelligence to aid SOC teams and forensic investigators.

While the aforementioned defenses are not by any means exhaustive, they help to illustrate some of the measures we can take to safeguard against attack.

About HiddenLayer

HiddenLayer helps enterprises safeguard the machine learning models behind their most important products with a comprehensive security platform. Only HiddenLayer offers turnkey AI/ML security that does not add unnecessary complexity to models and does not require access to raw data and algorithms. Founded in March of 2022 by experienced security and ML professionals, HiddenLayer is based in Austin, Texas, and is backed by cybersecurity investment specialist firm Ten Eleven Ventures. For more information, visit www.hiddenlayer.com and follow us on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Understand AI Security, Clearly Defined

Explore our glossary to get clear, practical definitions of the terms shaping AI security, governance, and risk management.